BRAVE HEART

Nobody believed that my charming husband was secretly abusive. Then, one harrowing night, he almost killed me. I knew he’d try again, so I ran. Eight years later, I’m still fighting for justice

By Ciro Muiruri

Portraits by Baljit Singh

January 31, 2023

I was born in a bustling Nairobi slum called Kawangware. Vendors lined every inch of its narrow streets, selling meat, fruit, fish, used clothes, cheap dishware and more. It was never quiet there. The air was always filled with sounds of haggling shoppers and shopkeepers, soaring music from the market stalls, and honking matatus shuttling people from one destination to the next. As a kid, I would run through the winding streets with my friends, playing with toys we made out of trash. We teetered on tin-can stilts, raced old tires and hurled ourselves across open sewer trenches. For years, it was the only world I knew. It was only later, when I was no longer a child, that I came to see the slum as a place where bad things could happen—a place from which I needed to escape.

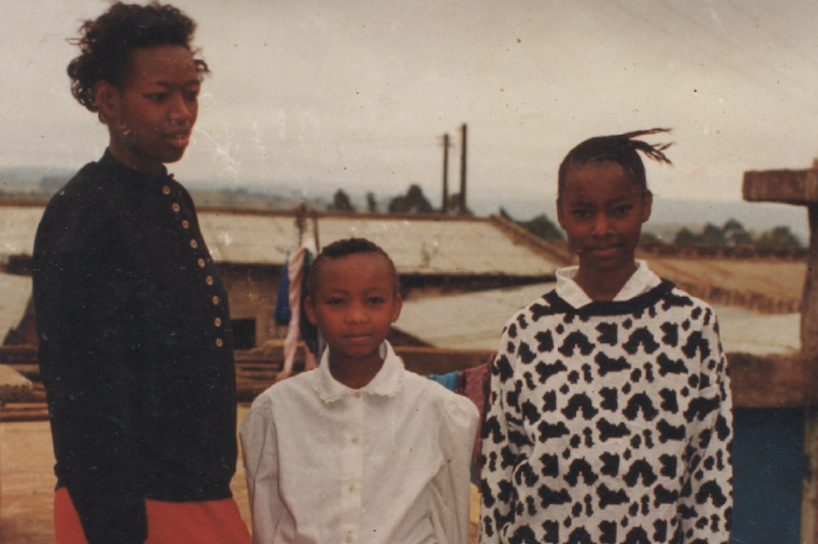

My mother finished high school, but my father dropped out in his final year. At 19, my mother became pregnant with me. My sister, Minneh, was born the year after I was. My mother worked as a hairdresser while my father waited tables at a hotel in Nairobi. We lived in a makeshift house constructed of scavenged timber and scrap metal. The roof was repurposed corrugated iron sheeting, and the floor was bare earth. My paternal grandparents lived next door. Both of my parents were determined to get me and my sister out of the slums. They knew that, if we were going to have a chance of succeeding, we needed a good education. My father made sure we never missed a day of school. While my parents fought constantly at home, school gave me a sense of order, discipline and peace. I took pride in doing my homework and learning to read.

When I was 11 years old, my parents split up and my mother moved out, taking me and my sister with her. Later that year, my mother found out that she had AIDS. She was so sick she could barely stand. My sister and I took care of her, feeding and bathing her. After several months, one of my aunts came to take her back to her home village. Our school was too far away, so my sister and I were left on our own. My aunt dropped by every week or so with some cornmeal and a bit of money for food. It fell to me to prepare our meals, wash our clothes and make sure we went to school every day. This new routine went on for nearly a year before my father learned about our situation and took us to live with him.

My mother died the following year, in 1998, when I was 13. I was devastated, but her premature death also felt like an important lesson: if I didn’t get out of the slum, I might encounter a similar fate. Soon afterward, I experienced another tragedy when my father revealed to me that he, too, had AIDS. In Kenya, there was a lot of misinformation and stigma surrounding the disease. HIV-positive people were shunned and ostracized. The hotel industry required employees to show their HIV status, which meant that my father couldn’t work. We got by for several years on the kindness of friends and neighbours.

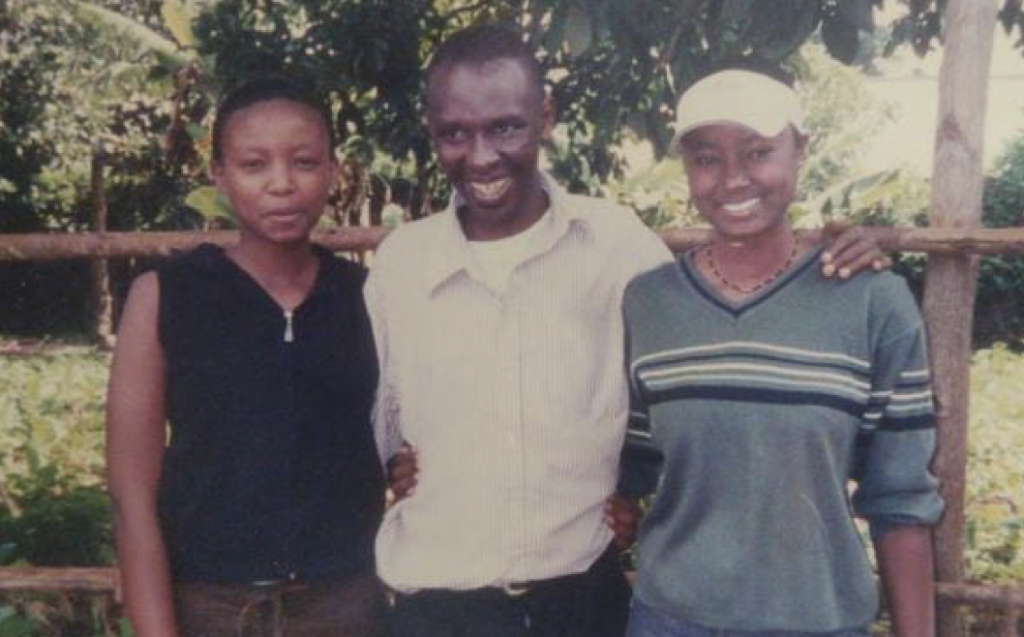

My father and I grew close in the final years of his life. It turned out that he had spent years saving up to buy a small plot of land outside Nairobi for my sister and me. His dream was for us to get out of the slums and live on the land. He had big ambitions for me and was always warning me not to end up like my mother and him. Education, he stressed, was the ticket to a better life. Yet he knew that the slum was a sticky, circular beast: you were born in the slum to parents who had been born in the slum; you married a boy from the slum and gave birth to children in the slum. Above all, he warned us to stay away from the vultures—his nickname for slum boys. Because of my father’s encouragement, I finished high school.

He died when I was 18, and I cried myself to sleep for weeks. I felt completely alone in the world without him. When I later got an opportunity to leave the slum, just like my father had always hoped, I jumped at it. A family friend in Nairobi needed a temporary au pair. I moved into an apartment in the upscale gated community where the family lived, and I spent my time looking after their toddler. The job lasted only four months—long enough for me to fall in love with life in the city. Soon afterward, I was hired at an internet café in the same neighbourhood. I couldn’t afford a place there, so I rented a small room in a nearby slum. I wanted to stay within arm’s reach of the world that my father and I had dreamed about.

I didn’t know then that it held its own invisible dangers.

i drained my chequing account to pay for everything jc insisted we needed. even with a job, i depended on him. if i needed anything, i had to ask him for money

I met JC at the café in 2005. He came in almost every day to use the internet—and to talk to me. I learned that he had recently moved to Nairobi for his job. He told me he worked at an international organization geared toward educating deaf children. He was divorced, with a young son back in Togo, and he lived in the same gated community where I’d worked as an au pair.

It was not love at first sight. I wasn’t attracted to him, and my father had instilled in me a deep fear of men and all that they represented—unwanted pregnancy, HIV, slum life. But JC was a master with words, and I was intrigued by his charming, confident personality. He was equally curious, wanting to know more about his new country, about life here, about me. Within a month, I decided to give him a chance. In contrast to the small world I’d come from, JC’s life appeared enormous, full of exciting, important people and big adventures. I was hungry for all of it.

For our first date, he cooked me dinner at his house. Over the meal, he asked if I’d had boyfriends and how many men I’d slept with. The answer was zero. His question mortified me, but I was proud of my virgin status, and JC praised my virtue, telling me that I was special. He also bragged about all the women who were interested in him—and yet he’d chosen me. I was scared of sex, and JC could sense it. He calmly assuaged my fears, telling me I had nothing to worry about. “You’re a big girl,” he said. I convinced myself that it was the right moment and he was the right person.

For the first time in my adult life, I felt worthy of love. With JC, I could have the life I’d always wanted—a life of possibility and adventure. He took me out to glitzy Brazilian steakhouses, where the food and expensive wine never stopped flowing, and showered me with luxurious gifts, like expensive perfume and a new wardrobe for my 21st birthday. He whisked me around in taxis, promising that I’d never have to take public transportation again. Nobody had ever treated me with such generosity. I thought I’d finally met someone who wanted to take care of me.

The relationship moved fast—so fast that I didn’t see the warning signs. JC made me feel like the most important person in the world, telling me multiple times a day that I was everything he was looking for in a woman. But, just as I started to feel comfortable with his extravagance, the affection stopped.

JC would reprimand me for small things, like chewing too loudly. He would become cold and unresponsive without warning, making me wonder if I’d done something wrong. Other times, he’d say that strange men were staring at me in public and then accuse me of knowing them. I was terrified that he would leave me for one of the many women he always claimed were chasing him. My confidence deflated and my insecurities grew.

After we had been dating for a few months, JC offered me a job as a field officer at his organization. If I accepted, I would act as a liaison between the organization and a school for deaf children. The position would pay me three times what I was earning at the café. But there was one condition: because JC would be my boss, I had to choose between the job and our relationship. I chose the job easily.

I needed the money to support my sister, who was in college, and my grandparents. While I craved the security the relationship provided, what I wanted more than anything was independence.

My new job took me to another city, about a six-hour drive from Nairobi. I spent my days checking up on the students and teachers and reporting back to JC on how they were doing. Every couple of months, I travelled back to Nairobi, where I would stay with JC—despite his condition that it had to be him or my job. On one of those trips, he asked me to move in with him. He said the organization would understand because he was in love with me. I was everything he wanted, he said. I was touched. He was the only man I’d ever been with, the only person who’d ever taken care of me. So I agreed. He was now my boss and my boyfriend, and my whole world revolved around him. At the time, I felt fortunate. I’d soon learn that I no longer had a way out.

jc tried to control my life. he dictated what i wore, where i went and whom i saw. whenever i pushed back, he reminded me of what he’d done for me

Early in our relationship, I got pregnant but miscarried. I was secretly relieved. I feared that, if I were saddled with a baby and had little money of my own, my dreams for a career would be over before they’d even started. Then, a few months after moving in with JC, I became pregnant again, but this time was different. I had a secure job as an educator for deaf children in Nairobi, and I felt better equipped to face the prospect of motherhood. JC and I were married in a traditional ceremony, and in January 2007, at age 21, I happily welcomed our daughter, Naima, into the world. To accommodate our growing family, we purchased a plot of land just outside the city and began construction on a house. It was a peaceful, hopeful time in our lives, but it was short-lived. A few months later, I was looking for a blank videotape and instead found a recording of JC kissing a naked woman in our bed. Blood rushed to my head. The naïve belief I’d had in the sanctity of our relationship was shattered. When I told JC what I’d discovered, he begged me to forgive him and promised me that it would never happen again. I wanted to believe him.

In 2009, we moved into our new house. It was a difficult transition for me. At our old apartment, I’d had friends nearby. Now, the few neighbours we did have were out of reach, and I felt cut off from the city life I’d grown to love.

It didn’t help that JC was now controlling my finances. It started innocently enough: after hearing him complain constantly about his expenses, I offered to pay for our groceries and household supplies. Soon, I was regularly draining my chequing account to buy everything JC insisted we needed, including paintings and other superfluous decor. He always made sure that my salary was used up by the end of each month. So, even though I was working, I was dependent on him for cash. If I needed money for anything, I had to ask for it.

JC and I fought constantly—at home and at work. I found more and more evidence of his cheating, but when I confronted him, he always had an explanation. The condoms in his car belonged to a friend who had borrowed the vehicle; the eyeshadow in the passenger-side door had been forgotten by a colleague to whom he’d given a ride. Once, I was unpacking JC’s bags after a business trip and saw a receipt for women’s perfume. He had bought three bottles but given me only one. When I asked him where the other two bottles were, he acted shocked. He grabbed the receipt and said, “What? She charged me for three bottles? I only bought one!”

I felt confused, isolated and, worst of all, like I was being ungrateful for everything he’d given me. This fear was reinforced when I confided in my friends and relatives. Instead of expressing sympathy, they swiftly reminded me of my good fortune. They weren’t being deliberately malicious. In Kenya’s patriarchal society, boys are taught to be sexually adventurous and aggressive while girls are trained to be chaste, compliant and domestic; wives are expected to keep their husbands happy, and husbands can have sex with their wives without consent.

In moments of self-doubt, I wondered if I had failed to satisfy JC and had driven him to cheat. I was just a slum girl when he found me, and now I was living most Kenyan women’s dream. “Divorce is un-African,” my friends said. “A good African wife knows how to keep her marriage together.” Even though I knew something was wrong, these ideas were so deeply ingrained in my psyche that I had a hard time figuring out what to believe. I gave up asking JC why he always came home in the middle of the night, why I kept finding receipts for things that never made it into our house. I learned to live with the constant uncertainty, stress and worry of being his wife.

My education was one of the few things I had that was completely mine, and it gave me a reason to keep going. After Naima was born, I enrolled at the International Montessori College. I wanted formal training to further my work as a teacher and an administrator. Plus, I had recently been tasked with helping to open a school for deaf children in Nairobi, in one of the largest slums in Africa. I graduated in 2010, and with the newfound independence that my education provided me, I quit my job with JC’s organization and started my own private Montessori school in Ngong, near our new home. It gave me some measure of freedom from JC—though he fought hard to control me. He tried to dictate what I wore, where I went and whom I saw. He would frequently insult my appearance, demanding that I change my clothing if I wore something he deemed too short or too tight. He imposed a daily curfew of 5 p.m., which gave me just enough time to drive home from work. I didn’t know it at the time, but he also placed trackers on my phone and car and installed software on my phone to intercept my texts and emails. He knew where I was and to whom I was talking every minute of the day.

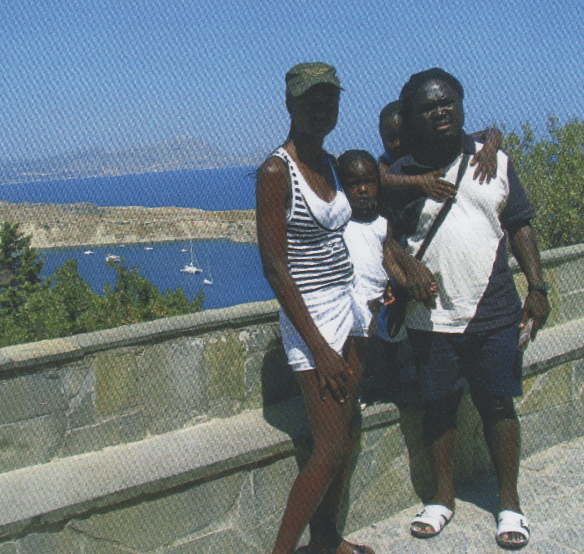

Whenever I pushed back, JC reminded me of everything he’d done for me: the college he’d paid for, the business he’d financed, the clothing and jewellery he’d bought. I grew despondent, unable to eat. At one point, I weighed less than 100 pounds. To the outside world, I had the perfect life: I lived in a large house with a beautifully manicured lawn and went on fancy vacations. But, behind closed doors, things were getting worse every day.

I was 24 when JC beat me for the first time. By then, we had been together for almost four years. From that point on, physical and sexual violence became a regular occurrence in our marriage.

I was terrified of JC and his temper. On one occasion, after another argument over his cheating, JC pushed me into our bedroom, locked the door and attacked me. He lifted me up and threw me across the room, sending me crashing into the bathtub. Then he strangled me until I nearly blacked out. My forehead was cut so deep that it needed stitches. But that day stands out in my mind for another reason. When JC left me bleeding on the floor, he forgot to take his phone. It rang, I answered and the woman on the other end introduced herself as JC’s girlfriend, Wairimu. I told her I was JC’s wife. She asked if my name was Tmah.

I soon learned the whole complicated story: Wairimu explained that Tmah was JC’s wife and that he and Tmah had a child together. I also found out that he was paying Wairimu’s university tuition and rent and had taken her on vacations and business trips. Wairimu knew that he was married—though not to me—and said she was only with him for his money. Soon after that call, I tracked Tmah down on Facebook and introduced myself as JC’s wife. We agreed to meet. She confirmed that she had a baby with JC and that she thought of him as her husband. She believed I was his ex-wife. Tmah had been to my home and had even met my children. I knew JC was a cheater, but discovering the extent of his lies made me sick. He’d been leading at least three separate lives.

My new knowledge of Tmah and Wairimu’s existence prompted another concerning thought: money. How could JC afford to support two households plus a girlfriend? I was convinced that he was stealing money from his employer. Doing some quick math, I calculated JC’s monthly expenses to be about 2.5 million Kenyan shillings—roughly $28,000 today—a lot of money anywhere, but a fortune in Kenya. My suspicions were soon confirmed when I found receipts for large, irregular wire transfers from his organization to his personal bank account.

When I confronted JC about Wairimu and Tmah, we fought brutally. I shouted everything I’d learned from her. My throat hurt, but the more I screamed, the more energized I felt. At one point, I walked toward the kitchen. JC followed, grabbed my shoulder, slapped me hard across the cheek and yelled at me to never use his phone again.

Something came over me that I hadn’t felt in my entire life—sheer rage. Without thinking, I rushed over to the bar beside the dining table, which was lined with wine, glasses, carafes and JC’s collection of cognac and whiskey. I swept my hand across the countertop and everything came crashing down. The bottles shattered on the ceramic floor, glass and liquor exploding across the room. “Well done, Ciro! Well done!” JC said, clapping and laughing hysterically. He took pictures of me and the mess on his phone.

I immediately regretted my actions. I’d just handed JC exactly what he wanted: photographic evidence that I was an unwell, unfit mother. Within a month, JC moved out and took Naima with him. I pleaded with him to leave her behind, but he just started shouting at me. I decided that I would seek help later, when it was safer, to get Naima back.

JC rented an apartment in a posh neighbourhood. He started telling everyone we knew that he was a single father and a victim of abuse, and they believed him. I felt worthless, lonely, empty. And JC wouldn’t leave me alone. He often showed up at the house unannounced, arriving in the middle of the night. He was convinced that I had lovers and that he would find them hiding, so he’d ransack the house. I went to the police for help, but it became clear to me that either they didn’t care or he’d bribed them to look the other way.

jc had beaten me so badly that i barely recognized myself in the mirror. My face had doubled in size. i had cuts and bruises all over my body

On the night of April 17, 2015, I was watching TV in the living room when JC let himself in. He had brought a sleeping Naima with him, who was quickly ushered upstairs to bed. I could tell that JC was agitated, but I still wasn’t prepared for what happened next. Without a word, he started choking me, demanding I confess that I’d been sleeping with other people. I tried to break free from his grip, but he was too strong. When he finally threw me to the floor, I played dead. It didn’t fool him for long. He punched me in the face so hard that I was sure my jaw was broken. I begged him to stop, insisting that I wasn’t sleeping with anyone else, which was the truth. He wouldn’t hear it.

He took my phone, pressed record and demanded that I list the names of everyone I’d cheated with. He told me he’d been monitoring my emails and had paid someone to follow me, and that they’d seen me get into a car with another man. That was true: it was an acquaintance who’d given me a ride home from the grocery store. If I refused to confess, JC said, he would put a knife through my stomach. He then dragged me to the bedroom, locked us in and, over the next several hours, physically and sexually brutalized me.

At one point, he told me that he could kill me and get away with it. I believed him. I begged him to stop. I begged God to make it stop. I was in excruciating pain. But JC only laughed. He told me, “Today you will be history.” Around 3 a.m., still in a blind rage, JC finally left the room and went downstairs to the kitchen. I could hear him rifling through the drawers. I knew he was looking for a knife.

My survival instincts kicked in and I ran to the study, opened the door to access a small balcony and climbed onto the roof. It was pouring rain. I shouted at the top of my lungs for help. The neighbours’ security lights flashed on. I could see JC, who had started to follow me out, retreat inside. The rain pounded my raw, naked body. Looking down at the driveway, I saw JC put Naima in the car and drive away, so I climbed back inside. It hurt to move, but I knew I had to. I wrapped a blanket around my body and walked to the bathroom mirror. I almost didn’t recognize myself: my head looked like it had doubled in size, my eyes were blood red, I had scratches and bruises all over my face, and my lips were swollen. I looked like I’d been hit by a truck. I needed to get to a hospital, but there were no phones in the house: JC had stolen mine. I had my school van, though.

I managed to drive myself to the police station. When I explained to the officer on duty that I needed to be taken to the hospital, he turned me away, saying that there must have been a good reason I was assaulted. “Enda ukalilie mamako,” he told me. Go and cry to your mother. I figured JC had driven to the station first to bribe the officers. From there, I went to the Nairobi Hospital. Doctors treated me right away; I was taken for an MRI and then admitted to the High Dependency Unit. I awoke a few hours later, horrified to find that JC had snuck into my hospital room. I started screaming and pressing the bedside emergency buttons. Security guards apprehended him and escorted him out of the building. From then on, there was a 24-hour guard stationed outside my room.

I was in the hospital for 10 days and required several surgeries, including one to repair my stomach and another to fix my eardrum, which had been ruptured. After I was discharged, I went back to the local police station in Ngong to press charges. About a week later, JC was arrested and charged with assault causing grievous harm. He was released on bail and told to appear in court within 48 hours. He didn’t show, but the police did nothing. He began to harass me, trying to get me to withdraw the case. He refused to let me see Naima and threatened to finish what he had started.

I tried to resume my life, including my work at the school, but I was too traumatized. I couldn’t sleep, and when I did, I had horrible nightmares. My life was in danger, and the police weren’t going to help me. More than anything, I wished to see Naima. Fed up, I reached out to a national TV news reporter and told my story. I hoped that going public would put pressure on the authorities to arrest JC and help me get my daughter back. I wasn’t afraid of the attention or potential backlash. The worst had already happened.

The story aired in May 2015, around the same time that JC was finally arraigned in court—only to be released shortly afterward. Soon, both he and the Ngong police department began pressuring me. The police threatened to arrest me under false charges. One officer told me that she could make me disappear. But I wasn’t ready to give up. I kept speaking out, appearing on another national TV segment. Eventually, in July, the gender-based violence division in Nairobi took on my case. JC was additionally charged with sexual assault.

But my victory came at a cost: in December, I received a credible tip from somebody in JC’s inner circle that my life was in imminent danger. I needed to get out of Kenya, at least for a few weeks, and I needed to do it immediately. Wanting to get as far away as possible, I reached out to a friend in Toronto, who invited me to stay with her. I had few other options if I wanted to live.

I arrived in Toronto in January. When my friend heard what I’d endured back in Kenya, she encouraged me to seek asylum in Canada. I learned that JC had recently fled Kenya, taking Naima with him, and remained a free man. I knew that, as long as that was the case, I wouldn’t be safe in my home country. He continued to tell me that I’d never see Naima again unless I cleared his name. I faced a painful decision. I could take my chances and return to Kenya, but what good would I be to Naima if I were dead? If I withdrew my case, as JC wanted, my safety was still not guaranteed—and what kind of role model would I be to my eight-year-old daughter? I wanted her to grow up to be the kind of woman who fearlessly stood up for herself. I moved to Sojourn House, a refugee shelter in downtown Toronto, started reading about refugee support groups in the city and began the process of applying for asylum. In May 2016, I was declared a Protected Person and was invited to apply for permanent residency.

JC was still keeping Naima from me, and I had no way of reaching her. I wrestled with guilt, torn between my desire to get justice and a desperate yearning for my daughter. I felt her absence like a void in my gut and often began sobbing when I saw young girls with their mothers. I was also struggling with severe PTSD from the attack—I was jumpy, always on edge. I started seeing a psychologist, who referred me to a program at the Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture. Slowly, with the help of a great therapist, my mental health improved.

In early 2018, I was hired as an administrator at a government office. I moved into a shared basement apartment for $500 a month. One of the things that kept me going—aside from a belief that I would someday see Naima again—was my school in Kenya. Without someone there to run it, it had closed. But, all these years later, I still had the small piece of land my father had left me. My grandfather suggested that I open a school on it, and he offered to help run it. I saved every penny that didn’t go toward rent or food. I began speaking to my friends and colleagues about the project, and to my amazement, many of them wanted to donate money. I started to really believe in myself when a co-worker donated $5,000.

By September 2019, I had enough money to open a four-classroom school on my plot of land. I ran it from Toronto, with help from the local community. But I still didn’t have a reliable major donor. To help fix that, I registered an official charity called Pendo International Projects. Now, individuals and businesses had the incentive of a tax receipt. Pendo has since grown to accommodate seven classrooms and 90 students ages three to six. This past fall, I received the prestigious Echoing Green Fellowship, which will provide me with $80,000 (US) toward my next goal: to franchise the Pendo school and develop a manual to help other women to build similar ones. I want to provide opportunities for young children and African women who are trying to overcome adversity and make a difference in their communities.

I believe that education saved my life. If I hadn’t learned to be self-sufficient when I was young, at school and at home, I wouldn’t have survived. That is the message I want to send to my community back in Kenya: that even an AIDS orphan from the slums who experienced horrible things in life was able to rise up, dust herself off and move on. In many ways, my life started anew in Canada. In 2016, I met and fell in love with a wonderful person. For the first time in my life, I’m in a loving, respectful and equitable relationship that’s built on trust and understanding. I owe much of what I’ve accomplished to my partner’s unfailing support.

Last February, I gave birth to our beautiful baby girl. The three of us live in the GTA, where I’ve embraced the cold Canadian winters by taking up snowboarding. I can even hack a double black diamond. I’d been put down for so long that I’d started to believe I was a lost cause, unworthy of love. For so long, I didn’t have the energy to enjoy life. But now I feel like I’ve been reborn and can do anything I set my mind to. I still think of Naima every day, and I often feel guilty for choosing my freedom and safety over her. JC has not allowed us to have any contact. Yet I remain hopeful that I will see my little girl again someday. When I do, I want her to look at me and think, Wow, I have a strong mama.

When contacted by Toronto Life as part of the fact-checking process, JC said that he is not guilty of all criminal charges against him involving the author in Kenya. He additionally denied the author’s allegations of physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

Portrait hair and makeup by Franceline Graham/Cadre Artists

This story appears in the February 2023 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here