Toronto, the old joke goes, has two seasons: winter and construction. Try to walk, cycle or drive anywhere in this city during the latter and you’re bound to end up snaking through scaffolding or yielding to an orange-vested worker holding a sign on a stick. If downtown feels particularly congested with pylons and hoarding right now, it’s not just your imagination. There are currently 250 cranes in Toronto’s skies, five times more than in any other North American city. The skyline is shooting up like bamboo.

For all the headaches this brings—the noise, the dust, the traffic—it’s also a good sign. Skyscrapers are sprouting across the city because people want to be here. More than 100,000 newcomers flock to Toronto every year, drawn by first-rate schools, well-paid jobs and an enviable quality of life. But each of those new arrivals needs places to live, work, shop and study. Ontario will need millions of new homes—the majority of them in the GTA—to make housing remotely affordable.

In Toronto, where space is at a premium, that means building up, not out. And the crucial task of erecting high-rises falls to the ironworkers, carpenters, electricians, crane operators and labourers below, who represent just a sliver of the GTA’s 200,000-plus construction workers. Every day, they rise before dawn, ascend into the sky and endure unforgiving conditions as they haul, pave, drill and weld. They transform mountains of concrete and steel into our schools and hospitals, our homes and offices. Their work is gruelling but rewarding—and more important than ever.

Previous

Next

“I was so petrified by the scale of the job that I couldn’t sleep”

Erik Millette, 43, tower crane operator

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

Aqualuna, the Bond, Corus Quay, Neptune, the One, Park Hyatt, PwC Tower

Erik Millette spends most days perched hundreds of feet above the city. Over the past 15 years, he’s manned tower cranes that loomed high above downtown office towers, condo construction sites—including Aqualuna, Neptune and the Bond—and commercial builds like Corus Quay. “I love how action-packed every day on the job is,” he says. “It’s incredible seeing the results of my hard work as a site goes from a hole in the ground to a beautiful, glistening building.”

In 2018, Millette began working on his most monumental project yet: the skyscraper known as the One, currently under construction at 1 Bloor Street West. Once finished, it will stretch 85 storeys, making it the tallest residential building in Canada.

Millette is the only person who operates the One’s electric tower crane, the largest currently in use in the GTA—it’s 30 metres tall now and will reach nearly 400 metres by the end of the build. “The night before my first day on the site, I was so petrified by the scale of the job that I couldn’t sleep,” he says.

Millette usually arrives at the work site around 5 a.m., performs a few safety checks and then climbs up to his cab, which he’s kitted out with a portable coffee machine. Then he begins hoisting concrete forms and steel columns, some as heavy as 52 tonnes, into place.

Every lift is a team effort. Before Millette moves anything, he coordinates with a site foreman and a group of workers known as riggers, who securely load his crane, as well as swampers, who act as his eyes and ears on the ground. Together, they plan a safe and efficient route for Millette’s hauls.

The stakes are high: virtually every trade working on the site—structural steel, mechanical, electrical—relies on the crane for day-to-day tasks. One bad lift can endanger people’s lives and set a project back months. “You really need to be dialled in because the job requires a lot of hand-eye coordination and attention to detail,” says Millette. “It’s mentally exhausting. I’ve seen many people bow out over the years because they couldn’t keep up.”

When he’s not in his cab, Millette stays active to offset the physical toll of sitting for upward of 12 hours a day. He grabs his skateboard and drives from Burlington, where he lives with his wife and two kids, to his favourite skate park, near Ashbridges Bay. “I’ve skateboarded since I was eight,” he says. It was once his dream to go pro. “But now, I’ve found a new dream job. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

Millette worries about the future of his profession. “In 10 years, a lot of the older generation is going to start retiring, and younger people aren’t as interested in the construction trades these days,” he says. “The work is hard, but salaries start at $80,000 a year and the demand is there. I can tell you first-hand that there’s nothing more exhilarating.”

Previous

Next

When Wassim Sharaf left Iraq, in 2003, he was broke. He settled in

Oakville and worked odd jobs to get by. Then a friend tipped him off to a

gig with good pay and reliable hours: general labour in high-rise

construction. Sharaf was a bit apprehensive—“I had never been higher

than maybe 10 floors,” he says—but decided to give it a shot.

Nearly

20 years later, he’s a veteran of the industry. He’s worked on condos

across the GTA, including the new towers in Regent Park and Solaris, a

41-storey building in Scarborough. His current job site is Avia, a pair

of residential buildings, 38 and 50 storeys tall, near Mississauga’s

Square One.

Sharaf is a general labourer and safety

representative, which means it’s up to him to make sure no one gets hurt

on the job. He’s on site by 6:45 a.m. and meets with each construction

team to review possible hazards, such as high winds or heavy rainfall.

He helps build safety scaffolding, supervises concrete pouring and

reminds workers to wash concrete off their skin—in the heat, it can

cause burns and blisters. Depending on the season, Sharaf will set up

fans to cool workers or salt the ground to make sure they don’t slip on

ice. He’s also the guy others call when something goes wrong. Once, he

had to perform CPR on a worker who fell and stopped

breathing—fortunately, the man survived.

Because safety

representatives interact with every type of worker on a job site, Sharaf

has picked up some knowledge of multiple trades. “I need to know what’s

going on with every sector,” he says. He’s learned various aspects of

carpentry and concrete finishing—that way, he can both ensure the job is

done safely and help out when workers need an extra hand.

His

long-term goal is to become a safety officer, a higher-ranking position

that requires at least three years on the job and special certification.

In that role, he’d inspect multiple sites, develop health-and-safety

strategies, and investigate workplace accidents and complaints. “It’s a

beautiful job when you care about people,” he says.

“When I started, I had never been higher than the 10th floor of anything”

Wassim Sharaf, 37, safety representative

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

Avia, Regent Park redevelopment, Solaris

Previous

Next

“My Fitbit sometimes says I’ve done 23,000 steps in a day”

Rokhaya Gueye, 46, carpentry apprentice

PROJECTS SHE’S WORKED ON:

Woodbine Casino, Tyndall University, The Well

After 17 years working in telecommunications with the same company, Rokhaya Gueye was laid off. Instead of looking for another job in the field, she decided it was time for a reset. She wanted something new, something challenging. As a single mother of two, she was handy around the house, installing doors and repairing windows. And, years earlier, she’d studied construction engineering at George Brown College and loved it.

She googled “construction skilled trades” and discovered a non-profit labour coalition that helps BIPOC people get into the industry. Through the non-profit, Gueye found a carpentry apprenticeship and, later, her first job: building concrete forms for the Woodbine Casino expansion.

Since August 2021, Gueye has been assembling scaffolding at the Well, a 7.8-acre development at Front and Spadina that will include offices, condos, shops and public spaces. At first, the work was daunting. “I used to be terrified of heights,” she says. “Once, last year, I was on the roof, crawling on my stomach because I was so afraid.”

Now, she’s as bold as a tightrope walker, gracefully balancing on narrow pipes as she and her team build platforms for painters, bricklayers and many other tradespeople. The trickier the build, the more Gueye relishes it. She enjoys the creative problem-solving involved in constructing scaffolding in tight, slanted spaces—as well as the physical demands. “It’s like you’re on a treadmill, running a marathon for a whole day,” she says. “My Fitbit sometimes says I’ve done 23,000 steps in a day.”

Off the clock, Gueye is determined to improve representation in the trades, conducting workshops with the non-profit Afropolitan to help women and people of colour enter the industry. “We don’t see enough BIPOC people,” she says. “Some parents from Africa and the Caribbean say, ‘Be a doctor’ or ‘Be a manager.’ The trades are viewed as negative.”

Gueye also speaks to students about what it’s like to work in the trades. Last year, she visited an elementary school and used architectural models of houses to explain her work. “When we were done, they were all like, ‘I want to be a carpenter,’” she says. “Hearing that gave me goosebumps.”

Previous

Next

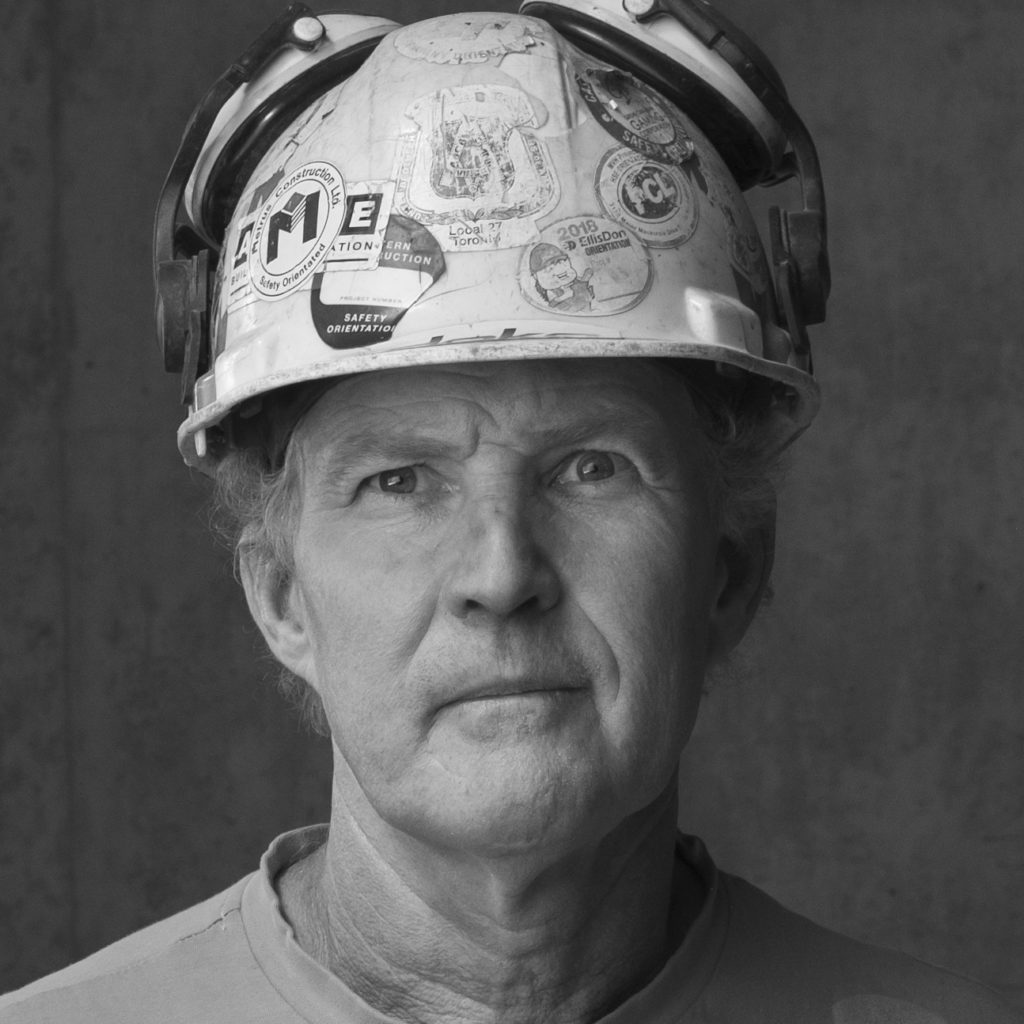

When Andrew McLaughlin was 12, his family left Belfast for Canada to escape the aftermath of the Troubles. He got a job driving snowplows, then an apprenticeship as an ironworker. He started at the literal bottom—his first job, almost 10 years ago, was building the underground tunnel to Billy Bishop Airport. Lakewater seeped through the walls and dead fish littered the floor.

At the time, his life was underwater too. He was drinking heavily, and a rocky relationship had sent him spiralling. His union covered a $15,000 35-day stay at a treatment facility for construction workers, but a year of relapses followed. He gained more than 100 pounds and drank himself into seizures and the beginning of liver failure. In late 2016, he was laid off.

The following year, McLaughlin got clean and revived his career, this time working on a condo at Bathurst and Lake Shore. He’d worked hard at his sobriety and improved his health, and he began to enjoy work—the cool breezes and panoramic views didn’t hurt—rather than fighting against it. “I’ve learned the ways of the force,” he says. He marked five years sober this past St. Patrick’s Day.

Ironwork involves laying rebar, the steel rods that reinforce brittle concrete. When the bars arrive on site, McLaughlin helps hook them up to a crane. Then he goes up to the work floor, where he and his team lift, lay and arrange the rods into grids that get drowned in concrete to become floors and walls.

It’s punishing work. This past winter, he tore his rotator cuff lifting 18-kilo steel bars above his head. (Afraid of appearing weak in the macho atmosphere of the work site, he hid the injury until a co-worker noticed, 45 minutes later.) He’s broken a foot and a finger and damaged three vertebrae. “I’ve got scars all over my arms,” he says.

But ironworking has its perks. He starts shifts before dawn, which provides sublime sunrise views. He began snapping shots of them, which has led to a side hustle in photography. (He’s done work for motorcycle dealerships.) Lately, he’s set his sights even higher: he’s training to become a commercial pilot and dreams of a career that marries flying with photography. “If I can find something like that,” he says, “the world would be my oyster.”

“I’ve got scars all over my arms”

Andrew McLaughlin, 33, ironworker

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

Concord Canada House, the LakeShore, Queen Richmond Centre West, the Rosedale on Bloor

Previous

Next

“You gotta have eyes in the back of your head”

Ken Windatt, 45, electrician

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

Concord Canada House, Eden Park Towers, Seasons

Ken Windatt was just 10 years old when he started pulling wires. His father, an electrician, enlisted him to help on the job and paid him enough to finance his GI Joe collection.

Thirteen years later, Windatt realized that those early experiences were the seeds of a lifelong career. He was lying in bed watching the fan spin and wondering about what made it go around. There’s a lot of work that goes into this, he thought. Seeing his father’s T4—he made $90,000 a year—sealed the deal. “I said, ‘Holy smokes, these guys make a lot of money!’”

Windatt has spent the 22 years since wiring up skyscrapers across the GTA. In high-rise buildings, the cords that power lights, stoves and Xboxes run through a network of conduits called raceways. During construction, Windatt places pipes in the walls and floors of the building, alongside the steel grids laid by ironworkers. After everything gets encased in concrete, he pulls electrical wires through the raceways, guiding them to light fixtures, outlets and switches.

It’s finicky work made exponentially more challenging by the elements. In the winter, at minus 10 degrees, Windatt has to arrange pipes and pull wires while constricted by bulky layers of clothes, his hands freezing in thin gloves. In the summer, when temperatures can exceed 30 degrees, he’ll wake up at 4 a.m. and get to work by 6 to beat the draining heat. The job can also be perilous. Windatt keeps a close eye on the cranes, which send massive loads of concrete and steel careening above him. “You gotta have eyes in the back of your head,” he says.

When he’s not on the job, Windatt is often in the woods near his home, in Courtice, just east of Oshawa, zooming around on a dirt bike. He likes to take his younger son, eight-year-old Chase, out on rides in his kid-sized off-roader. He’d be glad to see his kids continue in the family’s line of work, he says—if they play their cards right, they could retire at 55. Not him, though. “I spend too much money on toys,” he says. “I think I’ll have to stick it out a little bit longer.”

Previous

Next

Throughout the 2000s, John Eccleston made a living as a singer-songwriter playing pubs around Toronto. But, by 2011, he was tired of the gigging life. “I thought, I don’t want to be singing ‘American Pie’ in bars forever,” he says. He realized he’d enjoyed renovating his house more than hitting the stage, so he contacted a local carpentry union and found a job as an apprentice.

John’s work involves building forms—structures made from plywood, aluminum and composite materials. Other workers pour concrete and steel into those forms, creating the columns, beams and slabs that act as the bones of high-rise buildings.

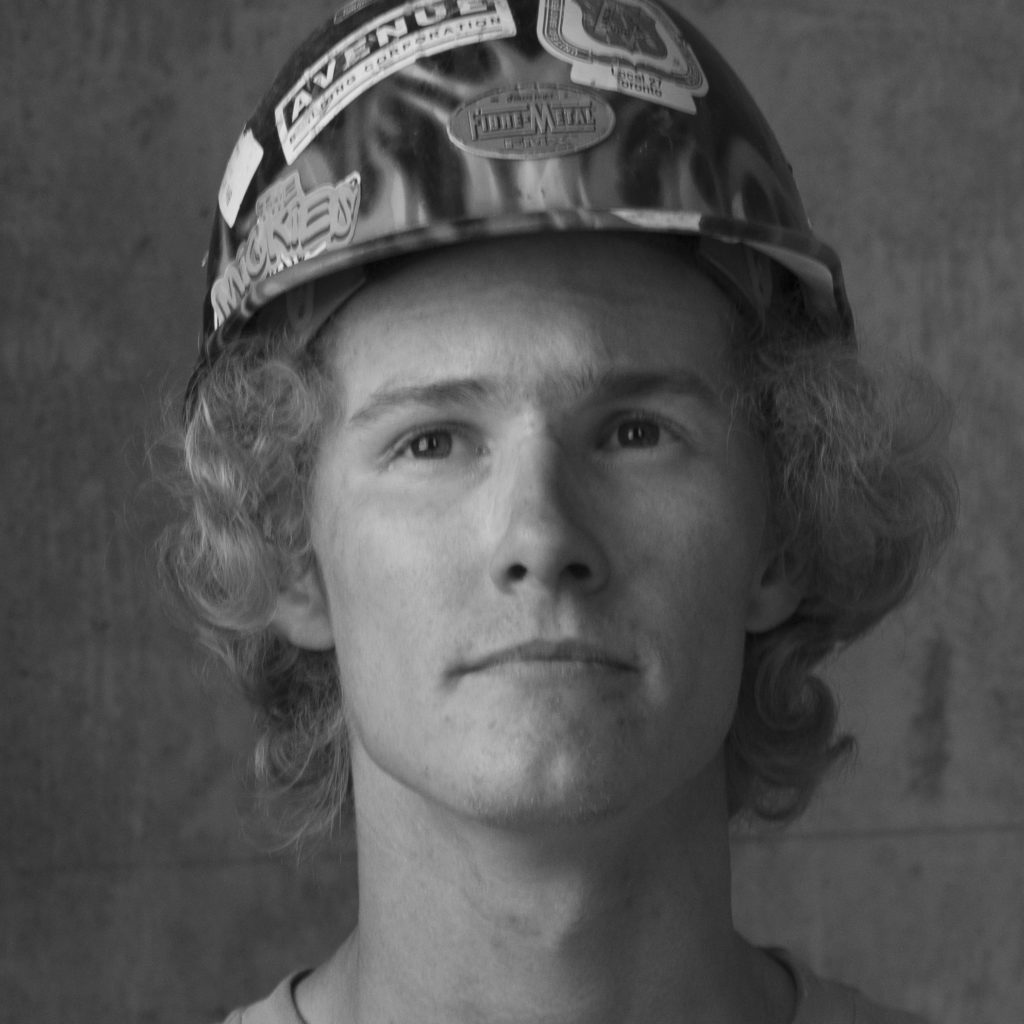

A couple of years ago, John’s son, Henry, dropped out of a philosophy program at Trent University and began working in restaurants. “I wasn’t bad at academia,” says Henry. “It just wasn’t for me.” Then the pandemic hit, and he found himself unemployed. John offered to get Henry into the carpenters’ union. “I couldn’t see a reason why not,” Henry says.

John and Henry now work together on the Celestica redevelopment at Don Mills and Eglinton, a 60-acre project that includes multiple condo towers, townhomes, office space and sports facilities. Once the site was cleared, they were among the first workers there, building forms that were instrumental in laying the project’s foundations.

In May of 2022, John’s union successfully negotiated a 12.5 per cent pay increase. In three years, both he and Henry will be making $55 an hour—more than $100,000 a year.

Henry has no definite plans to finish his philosophy degree. “Some of my old classmates are a bit surprised that I’ve gone into the trades,” he says.

He enjoys working alongside his dad. “I see him when he’s around his friends, doing something he loves,” Henry says. There are a lot of father-son duos in construction, according to John—parents often act as the next generation’s entry point into the trades. Without that connection, students tend to overlook the industry, John says. “A lot of people would rather make $60,000 a year and wear a shirt and tie.”

“Some people would rather make $60,000 wearing a shirt and tie”

John Eccleston, 56, concrete formwork carpenter

Henry Eccleston, 25, apprentice

PROJECTS THEY’VE WORKED ON:

Maple Leaf Gardens, MaRS, IBM redevelopment

Previous

Next

“If you never try, you’ll never know what you’re capable of”

Rony Barbosa, 42, shop steward and safety representative

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

Charisma on the Park, Glas, M5V

Rony Barbosa never saw himself working in an office. As a young man in Portugal, he enlisted in the army and then worked as a bartender. When he moved to Toronto, in 2002, he got a summer job paving sidewalks. Then his union, LIUNA Local 183, asked if he’d be interested in full-time work paving something a little loftier: high-rise apartment buildings. He was afraid of heights, but the pay was better, so he decided to go for it. “If you never try, you’ll never know what you’re capable of,” he says.“You just have to deal with your fears.”

That decision kicked off 12 years in high-rise construction. Earlier in his career, Barbosa was responsible for pouring concrete into forms prepared by carpenters, creating the floors and walls of buildings. A crane would lift those hardened structures and drop them into place. He’d repeat the process, floor by floor, until the buildings were complete.

Barbosa has worked on a handful of buildings across the city, including the Glas and M5V condos along King West. Today, he’s working at Charisma on the Park, a two-tower development just north of the city limits on Jane Street.

His days start early: he leaves his west end home at 5:45 a.m., grabs coffee and then drives up the 400. Once on site, he has two roles. He’s the shop steward, the worker who acts as the face of the union. This entails disseminating information from the union, ensuring that the employer is following the collective agreement and representing fellow members in complaints. He’s also a safety representative, which means that, on any given day, he might be replacing dead light bulbs or repairing broken fencing. Every evening, he helps tie down materials that could blow away. And, in the summer, he spends a lot of his time handing out water bottles to make sure his co-workers stay hydrated.

Barbosa says his favourite part about working construction is driving through the city, seeing buildings he’s worked on and talking to the residents who now call them home. “That’s a beautiful feeling.”

Previous

Next

When Ron Browne graduated from high school, in 2007, his uncle suggested that he become a mobile crane operator. As opposed to tower cranes, mobile cranes move around and come in different sizes and configurations for different kinds of tasks.

To get the job, Browne had to complete two months of in-class training and 6,000 hours of on-the-job training as a paid apprentice. He worked a variety of jobs: building condos, installing utility vaults for Toronto Hydro, replacing cellular antennas for Bell and Rogers.

He’s currently working on One Yonge condos, where he has helped install the construction elevators, windows and glass panelling. He also helped assemble the site’s tower cranes—first pouring the concrete foundations and then fitting steel components together, piece by piece.

“Crane operators spend most of our shifts sitting in our cabs, so a lot of people think we have the cushiest job on a construction site,” says Browne, laughing. “People don’t realize how much constant focus the job requires.”

Browne’s gig comes with long hours: 16-hour shifts aren’t unusual. Being outdoors is a different challenge—or perk—depending on the job. “I can be working on a waterfront site and enjoying the lake breeze one week and spending 12 hours underground working on the Eglinton LRT the following week,” says Browne.

On his days off during the summer, Browne takes out his 6.4-metre motorboat and surveys the skyline he helped build. “It’s a special feeling to be part of shaping Toronto’s future,” he says. “I’m excited to see our city grow in the decades to come.”

“People don’t realize how much focus the job requires”

Ron Browne, 31, mobile crane operator

PROJECTS HE’S WORKED ON:

L Tower, One Bloor, Pinnacle One Yonge, Eglinton Crosstown LRT