THE EDUCATION OF ELON MUSK

Before he was the egomaniacal, influential and just plain weird owner of SpaceX, Tesla and Twitter, he was an awkward kid who built computers and chased girls at Queen’s University.

THE ONTARIO YEARS OF THE WORLD’S MOST ABSURD BILLIONAIRE

By Haley Steinberg

January 3, 2023

Few people draw as much attention to themselves as Elon Musk.

In some ways, he can’t help it. When a person is worth about $150 billion—making him, at age 51, one of the wealthiest individuals on the planet—people are bound to be curious. But Musk is also the type of guy who wants you to look. The type of guy who, in April 2022, struck a $44-billion deal to buy Twitter, bragged that he did it so he could “help humanity,” then spent the summer very publicly trying to get out of paying up. The type of guy who, two days before finally closing the headline-making purchase in late October, changed his Twitter bio to “Chief Twit” and posted a video of himself walking into the company’s San Francisco headquarters carrying a white porcelain sink, captioning it, with a resounding comedic thud, “Let that sink in!” And the type of guy who proceeded to ruthlessly jettison half of his inherited staff, ominously warning everyone else to work harder (something he calls “being hardcore”). Musk is so odd, so ambitious and so mercurial that it’s easy to forget he’s also brilliant. Can all of those extremes coexist in one human? Normally, no. But Musk is not normal. He’s earned nearly everything he has by being smart—and by possessing a lifelong, near-maniacal sense of self-belief.

Musk is like an alien doing his best impersonation of a human. Unsurprisingly, he has always been somewhat of an outcast. He was born in Pretoria, South Africa. His mother, Maye, was a dietician and model. (She’d go on to become a CoverGirl and appear in a Beyoncé video.) His father, Errol, was an engineer who worked in property development and emerald mining. Musk has said that he was raised first by books—particularly Isaac Asimov’s Foundation sci-fi series—and then by his parents. When he was eight, they divorced. Musk and his younger siblings, Kimbal and Tosca, went to live with Maye. By the time he was 10, he’d started to feel sorry for Errol, who seemed sad and lonely without his family. Musk decided to join his dad in Lone Hill, a suburb of Johannesburg. The move turned out to be a terrible mistake. Musk has since described his father as someone who “will plan evil.” Errol, in his defence, has said he’s been accused of many things, among them being a “rat” and a “shit,” but stresses that he loves his kids. (Musk once tried to mend things with his father as an adult, but it didn’t go well. He has since severed their relationship.)

School was hardly a respite. Musk was mercilessly bullied as a teen. While his nerdy exploits hinted at his nascent talent—by age 12, he’d sold a space-themed PC game called Blastar to a computer magazine for $500—they weren’t exactly cool. Plus, he was small, the youngest in his class, and he struggled to fit into the school’s macho culture. Gangs of kids hunted him through the hallways, intent on pummelling him. Once, a group of brawny boys threw him down a set of stairs, resulting in a trip to the hospital and a week out of school. The constant harassment didn’t ease until Musk turned 16, hit six feet and began learning karate, judo and wrestling. After puberty, he got into a fight with the biggest bully in his school and, at least in Musk’s telling, knocked him out with a single punch. It taught him a lesson: never try to appease a bully; it’s better to slug them in the nose. (The irony, of course, is that these days Musk is the bully.)

At 17, he fantasized about escaping apartheid-era South Africa, moving overseas and chasing the American dream. Canada was the closest he could get, at least initially. Maye was born in Regina, and branches of her family remained scattered across the country. Musk’s plans hinged on staying with a great-uncle in Montreal—a man who, he discovered upon landing at the Montreal airport in June 1988, had since moved to Minnesota. Unbothered, Musk bought a cross-Canada hop-on, hop-off bus ticket for $100. He travelled over to Swift Current, Saskatchewan, and hitched a ride to his second cousin’s house, where he got to work shovelling out grain bins at a nearby farm. When that got old, he moved on to splitting logs in Vancouver and then cleaning a lumber mill boiler room for $18 an hour. But hard labour wasn’t what Musk envisioned for his future.

Two years later, in the summer of 1990, he landed a sales internship at Microsoft Canada, travelling around southern Ontario and meeting with potential clients. It was a slog, but Musk found the challenge invigorating. His boss, David Carter, expected the 19-year-old to be intimidated, at least at first, but he was fearless, excitable and wildly enthusiastic. Carter remembers him returning to the office at the end of each week carrying a stack of leads ripped out of the Yellow Pages. He’d circle every company he met with and scrawl his observations next to each. To break the ice with dealers, he’d do card tricks. He’d talk about any new technology to anyone who would listen. In the burgeoning tech world, Musk saw boundless opportunity. He’d tell his boss, You could do it that way, or you could build this new thing. Officially, Musk was just an intern, but he didn’t act like one. As Carter put it to me, “He didn’t shy away from having an opinion.”

Come fall, Musk was ready to start university. He debated studying either physics and engineering at the University of Waterloo or business and commerce at Queen’s University. After visiting both campuses, he chose Queen’s—not because of the academics but because it had more girls, and Musk didn’t want to spend his college time with, as he would later put it, “a bunch of dudes.” His next years in Kingston would prove to be formative. There, Musk met his first wife, Justine Wilson, his best bud, Navaid Farooq, and the fellow computer programmers who would go on to help him build his early companies. It was also where he contemplated the big ideas that would eventually turn him into the tech industry’s most controversial rock star: electric vehicles, solar energy, space travel and galactic colonization. By the time he finished his post-secondary studies, Musk had decided that he could do whatever he wanted. Make a fortune. Become famous. Shape the world.

In school, musk was awkward and seemed impervious to the feelings of others—Qualities that would later cause problems in silicon valley

Queen’s is one of Canada’s oldest and most prestigious universities. It was founded in honour of Queen Victoria by the Presbyterian Church, and its sprawling campus is dotted with limestone buildings that evoke both its religious and royal roots. Musk lived in the blander, newer Victoria Hall, a chunky X-shaped stone building that had, likely to his delight, gone co-ed in 1988. His dorm room was on the international floor, where Canadian students were paired with students from abroad. There, he met Navaid Farooq, a Geneva-raised fellow strategy gamer who remains one of his closest friends. Later on, Farooq would acknowledge that Musk didn’t make friends easily but was incredibly loyal to those he had. (Farooq is just as loyal—when asked for insight on Musk, he said he first needed Musk’s permission in writing. Musk himself never responded to interview requests.) The pair bonded over the video game Civilization, in which players lead their empires through several millennia, exploring, conquering and settling new territories. For the first time, Musk had found his ilk. “We were the kinds of people that can be by ourselves at a party and not feel awkward,” Farooq told Ashlee Vance, author of the 2015 book Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX and the Quest for a Fantastic Future.

At Queen’s, students and teachers alike respected Musk. They didn’t mock his ambitious ideas; they encouraged them. Unlike in high school, nerds weren’t considered losers. Musk was intense and competitive, interested and interesting. Even in a sea of genius strivers, he stood out. By all accounts, he wanted it that way. In his spare time, he entered public speaking competitions. To make extra cash, he created a small-scale computer empire out of his dorm room. He’d build customized tech—in his words, a “tricked out gaming machine” or a “simple word processor”—for cheaper than what you could find in a store, then sell it to students for a profit. His services also included removing computer viruses and solving general tech issues for other students. In his uniquely immodest way, Musk has said of that time, “I could pretty much fix any problem.”

In 1991, his brother, Kimbal, joined him at Queen’s. By then, the whole Musk family, minus Errol, had moved to Canada. Those who knew them at the time have described the Musk brothers as polite and ambitious, but Kimbal was the more personable and charming of the two. Elon, though enthusiastic and affable in his own way, could come off as awkward and impervious to the feelings of others—a quality that would cause problems, as well as successes, in his early Silicon Valley ventures. In their spare time, the brothers would pore over the Globe and Mail, pinpointing important people they wanted to meet. Then they’d cold-call them and ask them to lunch. This was how they came to know Peter Nicholson, a top executive at Scotiabank. It took the brothers six months to get on Nicholson’s calendar, but they succeeded. Nicholson was impressed by their gumption and ended up offering Musk a summer internship at the bank. There, Musk met a young finance whiz named Harris Fricker, who, along with a friend of Fricker’s named Christopher Payne, would go on to become one of the four co-founders of the online bank X.com, a predecessor of PayPal.

Another fateful meeting took place during this time. Justine Wilson was a fellow Queen’s student and an aspiring writer from Peterborough, Ontario. To an immediately smitten Musk, she was, as he later said, “the hot chick on campus”—smart, attractive and a black belt in tae kwon do. The feeling wasn’t mutual. Wilson has said that she was looking to fall in love with a motorcycle-riding, James Dean–esque “Romeo in a dark-brown leather jacket.” Instead, she got a clean-cut, baby-faced coder. He first approached her as she was heading up the steps to her dorm. He said he’d met her at a party, one she knew she hadn’t attended. Years later, Musk confessed that he’d noticed her from across the common room and orchestrated the chance meeting. He invited Wilson out for ice cream, and she agreed to the date. But, when Musk went to her room to pick her up, he found a note from Wilson saying she couldn’t make it. Hours later, after gathering intel on her whereabouts and favourite ice cream flavour—chocolate chip—Musk surprised Wilson in the student centre as she pored over her Spanish studies, two melting ice cream cones in his hands.

“The man does not take no for an answer,” Wilson later wrote in an explosive Marie Claire piece on their relationship. “I do think of him as the Terminator. He locks his gaze onto something and says, ‘It shall be mine.’ ” That was as true with girls as it was with everything else. Once, on a psychology exam, Wilson scored 97 per cent to Musk’s 98. The 1 per cent difference wasn’t enough to make Musk feel like the clear winner, so he went to their professor and successfully argued for a perfect grade. Wilson and Musk dated on and off for years. Whenever she seemed distant, he would double-down on his pursuit of her, calling nonstop. Her friends found him odd: when they tried to hug him, he’d just stand there, stiff and unresponsive, like a short-circuited robot. Still, Musk and Wilson married in January 2000 and went on to have six children: a set of twins and triplets as well as a son who died in infancy. (Musk now has nine children—in addition to those he had with Wilson, he has a son and a daughter with on-again, off-again paramour Grimes and another set of twins that he had in secret with Neuralink executive Shivon Zilis. He has claimed that the high number is because he needs to do his part to stave off “population collapse.”)

Despite excelling academically at Queen’s, Musk was dissatisfied. He wanted more and pined for the seemingly limitless potential of the US. One of his early acquaintances told me that Musk seemed to view his Ontario years as a stepping stone: “Elon was always looking for greener pastures.” He needed a playing field big enough for his grandiose dreams. So, only two years into his tenure at Queen’s, he made the jump to the American Ivy League, transferring to the University of Pennsylvania on a scholarship. He believed that a degree from an American institution would add jet fuel to his career. At Penn, he delved into solar power and alternative energy, writing dense papers and building concepts for a research database that resembled today’s online search engines. He also decided that he was done with student housing. He and his roommate, Adeo Ressi, now an entrepreneur, investor and Silicon Valley fixture who runs the Founder Institute, dumped their dorm and rented a large house. To help pay for it, the budding entrepreneurs turned it into a nightclub. On a good night, they attracted up to 1,000 people—though Musk himself was more likely to be holed up in his room gaming than partying.

He graduated from Penn with two degrees—a bachelor of science in physics and, from the university’s Wharton School, a bachelor of arts in economics—while also holding down Silicon Valley summer internships at a video game start-up and a company focused on space-based weapons and alternative fuel for cars. Initially, he planned to complete his PhD at Stanford, but despite being accepted, he never enrolled. That would have been the slow-and-steady route. It was 1995, the internet was beckoning and an impatient, determined Musk was ready to lay his claim to it. Kimbal, who had graduated from Queen’s, joined him in the Valley, and the brothers got to work. Their first order of business: recruit all the young, hungry, hyper-capable go-getters they knew from their time in Ontario.

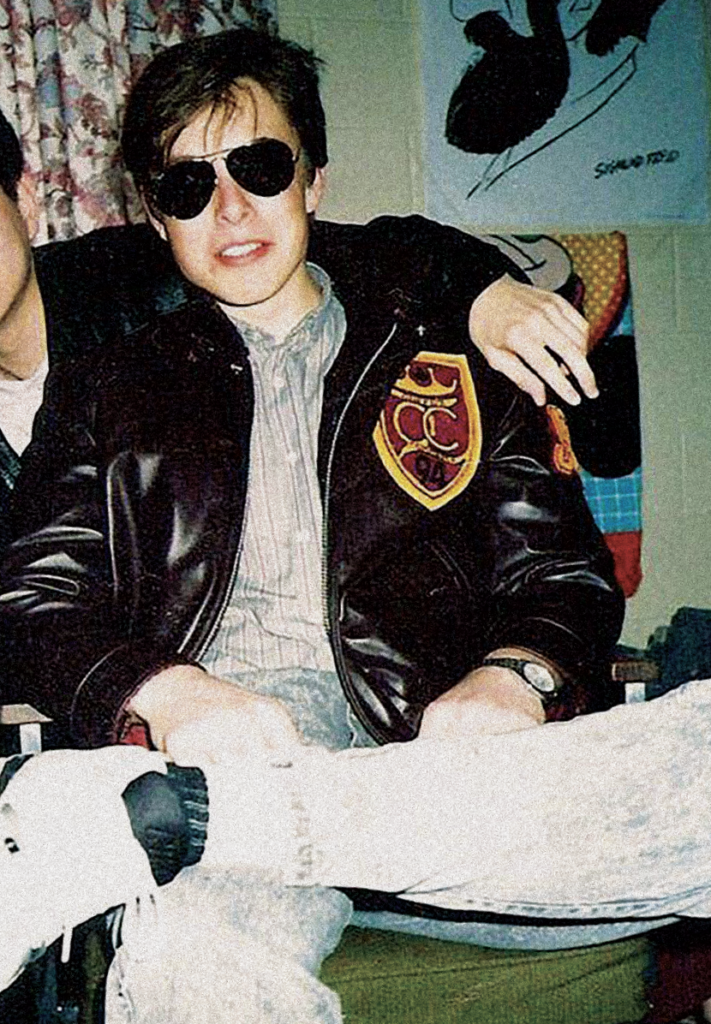

Musk celebrates his 18th birthday

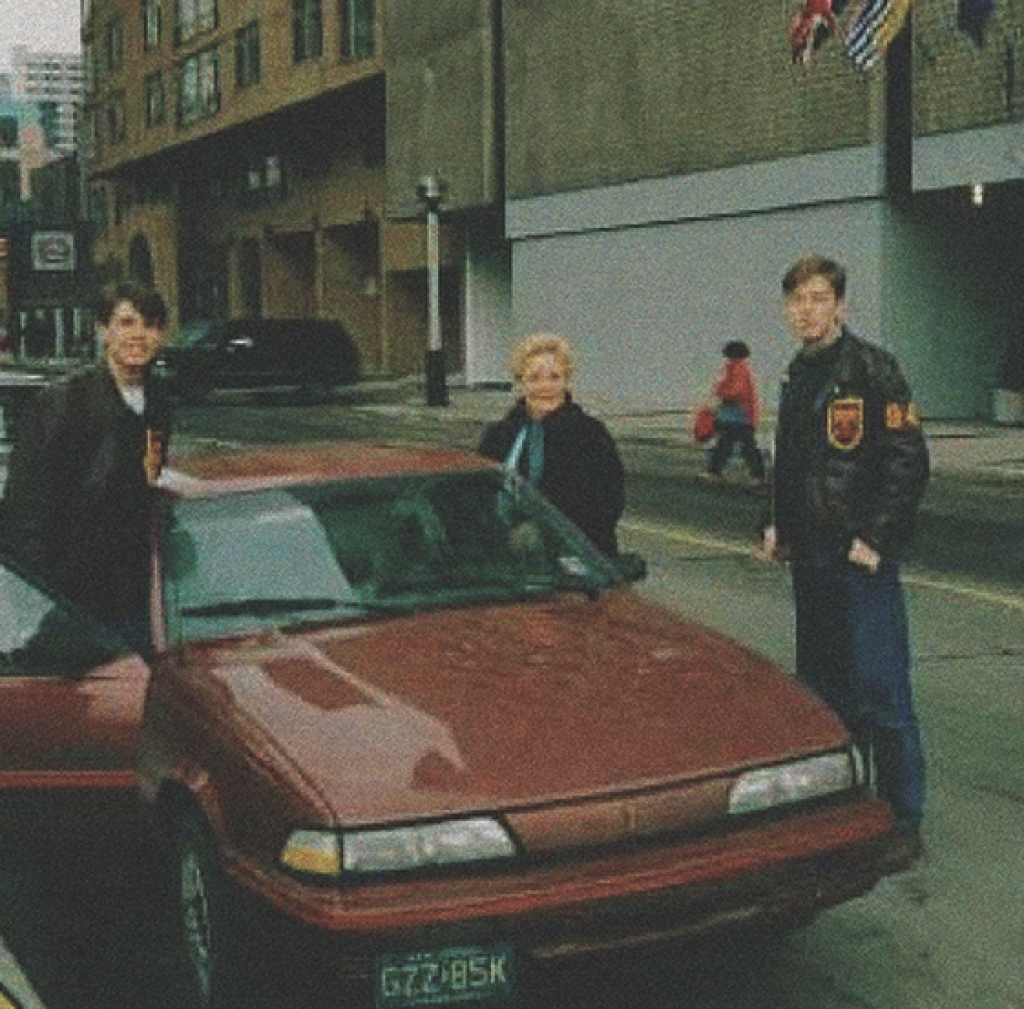

Musk poses with his brother, Kimbal, and their grandmother on a 1992 trip to Toronto

Musk pursued beautiful women on campus. Here, he’s with one of his university girlfriends, Jennifer Gwynne, and his mother, Maye, in winter 1995

ELON TIMELINE

The Musk brothers’ first venture was a searchable internet-based business directory that linked to online maps. They gave it a charmless and forgettable name—Global Link Information Network—but later rebranded as Zip2. The idea for the business, a mix of Yelp and Google Maps, came to Musk during one of his internships. There, he witnessed a fumbled pitch by a Yellow Pages salesperson about creating online listings and got to thinking about how to help businesses get on the internet. As usual, he was abundantly confident that he could pull it off. According to Vance’s biography, he told Kimbal, “These guys don’t know what they’re talking about.” He did.

Even in his early 20s, Musk had a relentless vision, which might explain how he was able to convince a bunch of Canadian college boys to ditch their prospects at other, more established institutions, hop across the border and join him in the dot-com boom. They were drawn not just by the breadth of his knowledge—business acumen as well as a keen mind for physics and science—but also by his unwavering, dog-with-a-bone focus. Musk wooed (or wore down) Queen’s classmates Michael Serbinis, Christopher Smith and Dominic Thompson into working at Zip2. Each would go on to achieve their own success, modest compared with Musk’s, huge by any other standard: Serbinis became the co-founder of Kobo and the CEO of the digital health platform League, Smith became a vice-president at Telus, and Thompson became a senior account director at a Colorado communications company. At the time, Serbinis was working at Microsoft’s campus in Redmond, Washington. Then, in 1996, the Musk brothers invited him to join them in Palo Alto—offering a couch to sleep on and a salary of $0.

But it was an opportunity to have a hand in building something from the ground up. Plus, Serbinis thought it sounded like fun. And it was. The timing couldn’t have been better: in 1996, businesses were clueless about the internet, and many didn’t see the point of even having a website. The Queen’s boys had their work cut out for them. They needed to convince retailers, restaurants, salons and other businesses to go where their customers would increasingly be—on the web. Today, Errol says he helped his sons kick off their business with a $28,000 cash infusion; Musk adamantly denies it, saying the money came from a small group of angel investors and their own hustling. Either way, the brothers were able to rent a tiny office space at 430 Sherman Avenue in Palo Alto, license a database of business listings in the Bay Area and purchase the necessary computer equipment. In a lucky break, Musk managed to score digital mapping technology, from a company called Navteq, for free.

He wrote the original code while Kimbal headed up the sales operation. Serbinis was one of the company’s first 10 employees. During his first weekend in Palo Alto, he worked 72 hours straight. That pace wouldn’t change: the small team worked constantly, always chasing funding and customers and rarely leaving the dinky Sherman Avenue space, where they ate and slept (Musk often on the floor). The office had unreliable plumbing, and its internet connection came via an Ethernet cable that Musk strung down the stairwell to the business below. Even though he was an immature 25-year-old with acne, Musk and his drive to make Zip2 prosperous spurred everyone else on. Several early employees attribute the company’s success to Musk’s Captain Ahab–like determination. As Serbinis has said, “He has an incredible, insatiable desire to win.”

Musk had a relentless vision. It helped him convince a bunch of canadian college boys to hop the border and join him in the dot-com boom

That doesn’t mean everyone enjoyed working with him. According to Serbinis, company culture “wasn’t big on Elon’s priority list.” Serbinis had grown up playing sports, and to him, the structure of a start-up was akin to that of a team. It was a group of people with clearly defined roles working together, not a hierarchy. But Musk didn’t see things that way. He was at the top, he had the vision and the plan to achieve it, and it was up to everyone else to fall in line. He was the textbook definition of a difficult boss. “What really surprises me is that he’s been as successful as he has,” an early Silicon Valley colleague told me. “He doesn’t have many of the qualities you’d see in a classic leader. But I guess that’s worked for him in some ways.”

Soon, the team had a working product, and venture capital funding followed. In early 1996, the California VC group Mohr Davidow Ventures invested $3 million in Zip2 and hired Rich Sorkin as CEO, pushing Musk into the role of chief technology officer. In 1999, Compaq Computer Corporation bought Zip2 for $307 million in cash. Musk’s take was $22 million, and he poured most of that into his next Silicon Valley venture, the online bank X.com. About a year after that, X.com merged with Peter Thiel’s Confinity to form PayPal. Musk’s early tenure there was marred by disagreements over his role and strategic vision, but that didn’t stop the company’s rise. In 2002, eBay paid $1.5 billion in stock for the company, a deal that netted Musk $165 million.

Those windfalls provided funding for everything that came next: SpaceX, which in turn begat Tesla and OpenAI and Twitter. Lately, Musk makes headlines not for ground-breaking entrepreneurial exploits but for personal and political controversies. Twitter, which has given him his biggest platform yet, has a lot to do with it. Unlike an $80,000 Tesla, Twitter is accessible to anyone with an internet connection. It touches the lives of over 200 million daily active users. Musk has always wanted a global audience, and now he has it. In his first month as self-described Chief Twit, he reinstated Donald Trump’s account, told his 119.2 million followers to vote Republican and relaxed the site’s content moderation. Try to ignore him, and his antics will earworm into your consciousness regardless. We’re all waiting to see what he’ll do next.

For now, Musk appears to be operating Twitter in the same way as his earlier ventures—albeit on a much larger scale. He plucked the best and brightest from his Ontario circle to join him in Palo Alto, and at Twitter 2.0, he’s pulled from his employee pool at Tesla and surrounded himself with a small army of top software engineers. Anyone who isn’t down with the cause is disposable; if you’re not with Musk, you’re against him. That’s the way it’s always been. The big question is whether his tactless, tried-and-tested strategy will work once again. Musk may be the only one who believes he’ll steer Twitter successfully, but that’s all he’s ever needed.

This story appears in the January 2023 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here