THE

FIGHT

OF

MY

LIFE

THE FIGHT OF MY LIFE

When my wife and daughter were killed in Iran’s downing of Flight PS752, my life was thrown into total darkness. I will do whatever it takes to bring the corrupt regime to justice. The death of Mahsa Amini only intensified my resolve

BY HAMED ESMAEILION

PHOTOGRAPH BY ÉRIVER HIJANO

DECEMBER 2, 2022

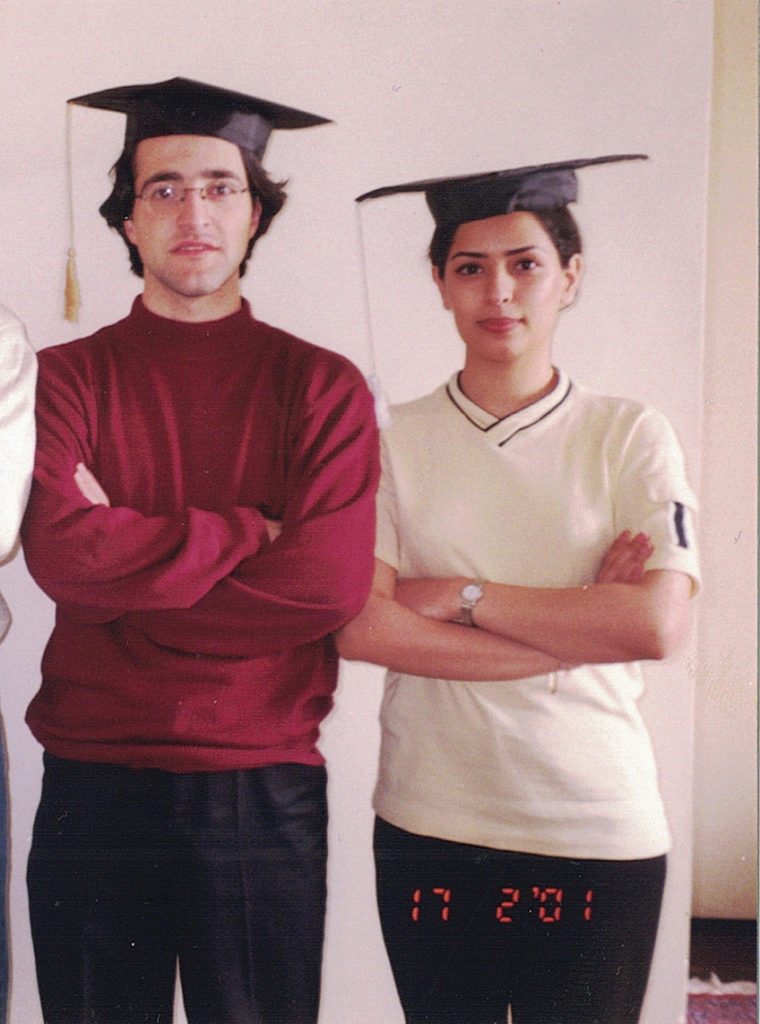

I first saw Parisa in the mid-1990s, while she was standing in line to register for dentistry school at Iran’s University of Tabriz. I was enrolling in the same program, and I was immediately drawn to her style. The regime of the Islamic republic, which had swept into power during the 1979 revolution, mandated that all women and girls over the age of nine wear a hijab in public. If they refused, they risked fines, lashings and imprisonment. Women also had to wear manteaux—long, loose coats that covered everything—and stick to modest colours like black or grey. But Parisa often wore little splashes of red or a cream manteau over jeans. Her glasses were framed in white. It wasn’t enough to cause trouble, just enough to signal her feminist beliefs. These choices, by the woman who would later become my wife, were quiet acts of rebellion.

Parisa was with her father, a conservation officer, who, per another regime requirement, was acting as her guardian. Her mother, a teacher, had planned to join them, but the authorities didn’t approve of the way she wore her hijab and turned her away. They’d travelled from Sari, a city in northern Iran where Parisa grew up with her two younger siblings. My own father worked for the national oil refinery company. I grew up in Kermanshah, a city in the west that was one of the centres for Iran’s oil industry. We were both 18 when we started university, both tired of living under a fundamentalist regime.

Under the Islamic republic, girls could be forced into marriage at 13, and they couldn’t marry without a male guardian’s consent. They couldn’t obtain a passport or travel without their husband’s permission, and they couldn’t seek divorce. Women were banned from being judges and serving in top positions of government. They couldn’t appear in public with a single man, unless they were related, without risking consequences. The morality police enforced the rules, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a specialized security and military organization, protected the regime and quashed unrest. Every Iranian knew that the police and the IRGC were always watching.

Over the first four years of university, Parisa and I rarely spoke. Sometimes we would pass each other in the hallways, wearing our white lab coats, but even as classmates, I couldn’t call her to talk casually. We would be kicked out of university—or worse—if we were caught. Still, I longed to get to know her. She was serious and studious, always getting top marks. She knew classic and modern literature and never held back her opinions. She advocated for the rights of women, children and minorities. Parisa saw me as a troublemaker. I was hotheaded and involved in everything except my studies. After the first year, no one expected me to graduate. I skipped school regularly to go to the cinema. I poured my energy into writing, angrily criticizing Iran’s politics, but I published under a pseudonym, afraid of what university authorities would do to me if they read my words.

By our fifth and final year of school, I couldn’t stop thinking about Parisa—especially her voice, which was soft and sweet. As the men’s class representative to the university administration, I was allowed to meet with the women’s class representative, who was friends with Parisa. At one of our meetings, I casually mentioned that I liked Parisa. The next time we met, the friend reported back: the feeling was mutual. For several weeks, Parisa’s friend acted as a messenger, eventually helping to arrange a phone call.

I didn’t own a phone, so one evening I went to a friend’s apartment at the appointed time, sat in the hallway and called Parisa’s dormitory. We knew that telephone operators monitored calls, so we had to watch what we said. I pretended I was her brother. We made plans to go for dinner. I had friends who specialized in arranging secret dates, and they told me of a pizza shop where we could meet upstairs without scrutiny. I worried that she wouldn’t come; all the courage required for our first date fell solely on her shoulders. As a woman, she took a great risk: she could be detained by police, fined, even arrested. She came anyway.

We stayed for three hours. I ate all the pizza. I would occasionally offer her a bite, and she’d shake her head. I blabbered about books, an audio recording of The Little Prince, university. We decided to tell our parents and a few friends about our burgeoning relationship—Parisa didn’t want to lie to her family—but agreed to keep it a secret at school. She would call me for 10 minutes or so every few days, and that was it. I would reorganize my day at the university to catch a glimpse of her. I’d go to the prosthetics lab to joke around with my friend because I knew she’d be there making plaster moulds for her patients. By summer, I was so deeply in love that I couldn’t bear to go a single day without seeing her. I wrote about my love for her in my diaries and gave them to her. I quit smoking because she didn’t like it.

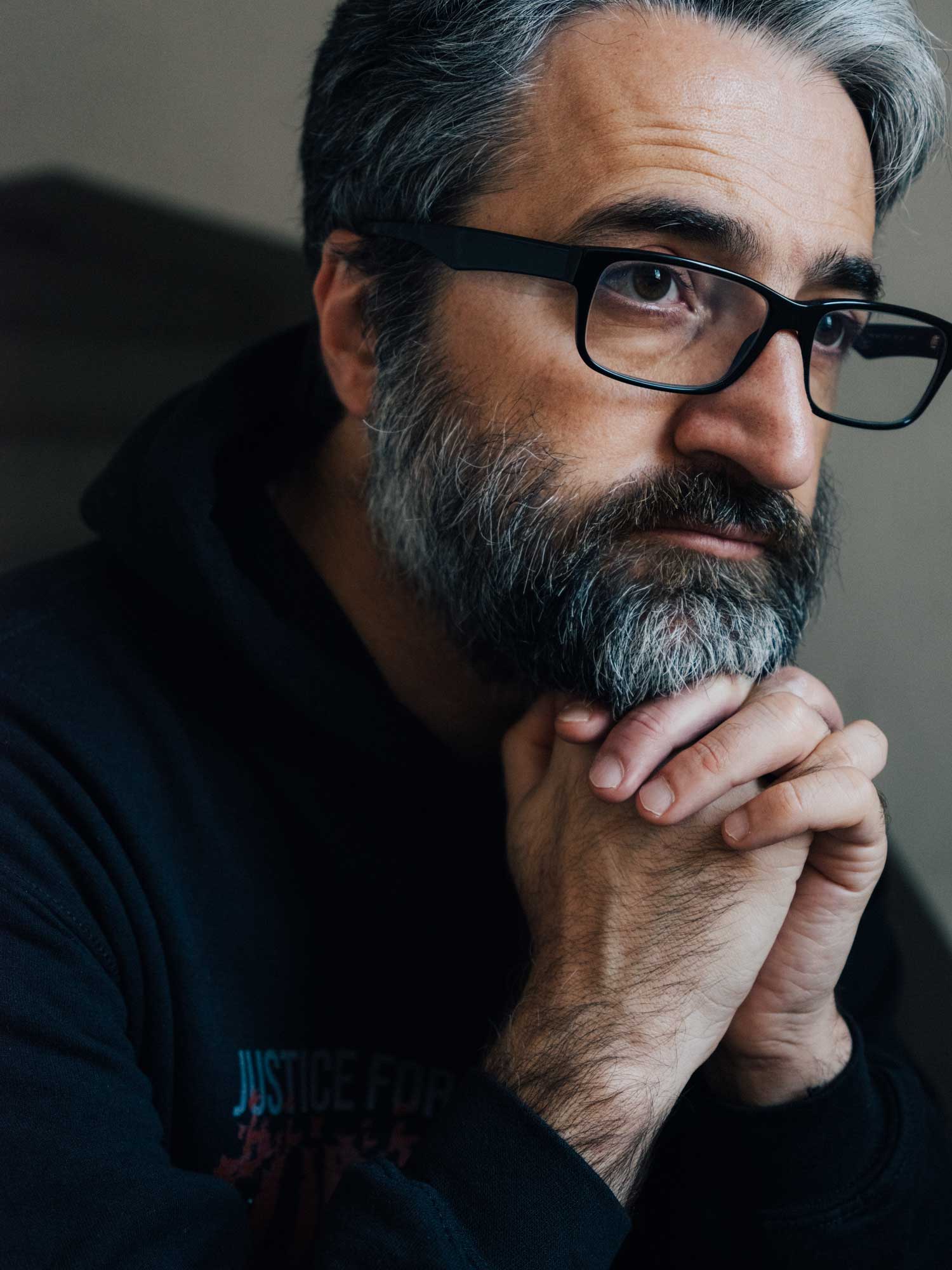

Left: the couple one day before graduating from dental school at the University of Tabriz

Below: a young Parisa in Sari, where she grew up

The couple one day before graduating from dental school at the University of Tabriz

Parisa and I arranged a secret date to meet for pizza. As a woman, she took a great risk in coming to see me

A young Parisa in Sari, where she grew up

At the time, arranged marriages were common in Iran. We wanted to break that tradition, but we still wished for our parents’ approval. After one year of dating, I travelled with my parents to visit her family so they could meet and consent to our marriage. Full of nerves about the day, Parisa and I had debated what to do about shoes as my family entered her family’s house. Parisa hated when people left their shoes on in someone’s home. She thought it unsanitary. We agreed in advance that my family would remove theirs as a sign of respect. She appreciated the gesture, and my parents instantly loved her.

On the way back to university the next day, I was waiting at the bus terminal, elated as I thought about our future, when I heard her voice: “Mr. Esmaeilion?” I laughed. She was always so formal. I used to tease her, “When are you going to call me Hamed?” We had one hour together as we waited for our buses. Now that we were engaged, we could walk and sit together without fear. If we got arrested, we could tell the police to call our parents.

Following graduation, I did the standard military service for men, and she did the public service required for women, each lasting two years. During that time, we started planning our wedding. On our invitations, we omitted the typical opening phrase: In the name of God. Instead, we chose a stanza from feminist Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad, whose work had been banned in Iran after the revolution: “If you come to my house, friend, bring me a lamp and a window that I can look through at all the happy people.”

We were married in 2003. Afterward, Parisa suggested that we move to Canada for a better life, free of interference from the republic. But I was a revolutionary in my own way. I was adamant. “We have to stay here,” I would tell her. “We have to build this country.” I wasn’t alone. Many young people thought we could help restore democracy. I soon realized that this hope was an illusion. Shortly after our wedding, the conservative supporters of Iran’s new Supreme Leader for life, Ali Khamenei, won a spate of local elections, dashing my dreams.

The next day, Parisa and I went to see an immigration lawyer. It took almost six years for the paperwork to go through. On May 23, 2010, soon after our visas were approved, Parisa gave birth to our daughter, Reera, in Pars Hospital in Tehran. In Mazandarani, the local language in northern Iran, her name means “clever woman.” She was born healthy and perfect, all bright eyes and wide grin. We counted down the days until we could leave Iran, knowing that Reera would grow up in a place where she would never be forced to wear a hijab. She would choose whom she wanted to play with and what jobs she wanted to pursue. She would be free from the watchful eyes of the regime. Parisa and I would be too.

We arrived in Toronto on December 9, 2010. The blistering cold was a shock, but we were so happy to be free of the Islamic republic. Parisa never once put on a hijab in Canada. Instead, she wore yellow sweaters and bright sleeveless dresses. We settled in Don Valley Village, where there is a large Iranian community. We missed our families back home but never experienced the depression people often have when they immigrate to a new country. We didn’t give ourselves time to. Instead, we jumped right into working toward what we wanted to accomplish. Parisa convinced me that we should take the exam to get certified as dentists in this country. We made a pact: no parties, no shenanigans, just studying. For our first two years in Canada, we read and talked dentistry nonstop in our tiny apartment. One of us would sit at the table studying and the other would play with Reera, then we’d switch.

If Parisa couldn’t answer a question while we studied, she would get upset. She’d scour her Farsi and English textbooks to find a solution. And, whenever I grew frustrated, I’d ask her for help. After one year of studying, we took the exam in February 2012. Before we even got the results, Parisa started applying to become a dental assistant and going for job interviews. When we received our marks, six weeks later, she had scored 92 per cent. I got 83 and was quite happy with that. The three of us—me, Parisa and Reera—danced in celebration in our apartment.

Parisa got a job offer in Hanover, a small town of roughly 7,500 residents almost 200 kilometres northwest of Toronto, so we moved. In time, I started working as a dentist in Elliot Lake. I’d leave Hanover on Monday morning, drive six hours to my clinic, stay in a tiny apartment and return on Friday. At night, I kept writing, always about Iran. I’d published two books before we moved to Canada—short story collections, including one that won a prestigious literary prize in Iran. I wrote a third book, a novel, that was awaiting publication when we immigrated. The Ministry of Culture reviewed every word of a writer’s manuscript. They’d remove references to alcohol, to politics and to women and men spending time together. I still don’t know why that third book, which was finally published in 2014, wasn’t censored or banned. In it, I included a scene that I’d adapted from a true story told to me by an Iranian colleague. She’d had two brothers, both political activists, who were arrested by the IRGC. After guards tortured and murdered her brothers, they dropped their bodies down the family’s outdoor toilet.

Soon after the book came out, Parisa’s father had a heart attack. Her brother called us at 3 a.m. and said we must come back. We got on a plane the next day. I was nervous about what would happen to me because of the book, but I didn’t say anything to Parisa. She was already in enough anguish. After we landed, a man approached me by name at the airport and asked me to come with him to an office called the passport verification centre—in reality, an IRGC intelligence office. I was allowed to enter the country but had to present myself again later for questioning. They asked why I lived in Canada, and they wanted to know why I had written that scene. After a long day of interrogation, I made it home to Parisa’s family at 6 p.m. Her father died one hour later.

I spent the entire trip in fear. My wife and daughter were devastated by the loss of their father and grandfather. Meanwhile, I could not be there to support them. I would walk out onto the street and know I was being watched. The IRGC could arrest me anytime and put me in prison for no reason. I wasn’t sure I would ever be comfortable in Iran, but I refused to let the regime’s scare tactics stop me from writing. As someone living outside the country, I could write aggressively against the regime. I didn’t want to give that up. I told Parisa that, if I died suddenly, she should go to my publisher and ensure that all my writings would be printed. She memorized the publisher’s name. Once, she woke me in the middle of the night to confirm that she recalled it correctly.

In 2017, we bought a house in Richmond Hill and opened a dental clinic together in Aurora. Our parents would come and stay for months at a time to help with Reera. She was a beautiful girl, happy, funny and stubborn. I used to make her practise the piano for 30 minutes every day, and at nine years old, she came to show me something she’d found on the internet: a statistic that said 20 to 25 minutes a day was suitable for piano practice for a kid her age. I laughed and relented. As much as she disliked piano, she loved soccer. She used to play left-back, but just in case she was ever called on to switch roles, we reviewed the skills needed for different positions. Her real sporting triumph was on the monkey bars. She told me that she had beaten everyone in her class, girls and boys, at hanging off the bars during recess. She used to practise at home on a collapsible set we bought her.

A smiling Reera

Left: a smiling Reera

Below: the family enjoying a day together at Disney World in 2015

The family enjoying a day together at Disney World in 2015

Then, in 2019, Parisa’s sister, who is a doctor in Iran, called to say that she was getting married. Parisa was ecstatic and began planning her trip back for the wedding. We decided that it was too risky for me to go but that Reera would join her. Parisa bought tickets on a Ukraine International Airlines flight, which would take off from Toronto and then fly to Kyiv for a stopover before continuing on to Tehran.

As their departure grew closer, the situation in Iran intensified. On November 15, 2019, during what would become known as Bloody November, protests over fuel prices broke out around the country. The regime shut down the internet to block its depravity from the world’s eyes, but according to Reuters, as many as 1,500 protesters were killed. I asked Parisa not to go. I was scared that something terrible would happen and I wouldn’t be there to protect my wife and daughter. Later that night, I apologized. This was a once-in-a-lifetime celebration for her sister and family, and it was important to her. Over the next three weeks, we got Parisa and Reera ready to go. We bought gifts for everyone in Iran. We bought Christmas presents for Reera and wrapped them.

They were flying out on Christmas Day. We let Reera open one gift—a video game—that morning, with the promise that she could open the rest when they returned. She squealed when she opened it. We played for two hours before I drove them to the airport. I watched them walk away from me and through the doors into the passengers-only area. I stood there until Parisa texted me that they were through security.

I didn’t know then that this was the last time I would see my wife and daughter alive.

The conflict in Iran worsened over the next 12 days. On January 3, a US drone strike killed IRGC major general Qasem Soleimani at Baghdad International Airport. The rising tension between the US and Iran set off alarm bells around the world. I sat up late at night, watching the news, writing and worrying about my family. I wanted to re-book their flights to get them home early, but Parisa told me to stop fretting. She would see me at the airport in Toronto on January 8, as planned.

Finally, the day of their return arrived. Parisa and I spoke briefly when the taxi was on its way to pick them up at her mother’s house. I worked that afternoon at my clinic. After finishing with a patient, I glanced at Facebook and saw that Iranian forces had launched ballistic missiles at two locations in Iraq where American personnel were located. I thought about the last war between Iran and Iraq. It started in 1980, when Parisa and I were toddlers. For years, Iraqi jets relentlessly bombed my hometown. There were many days when I did not think we would survive. The war finally ended in 1988, in part because the US Navy mistook Iran Air Flight 655 for a fighter jet and shot it down. One of my neighbours, a middle-aged man, was among the 290 passengers and crew who were killed. I still remember seeing his memorial notice posted in the streets.

Thinking back to that period, I felt sick. For the first time in my career, I cancelled the rest of my appointments. I kept calling Parisa, but it was no use. Her phone did not have roaming. Eventually, I reached her sister, who said that they had checked in at the airport 10 minutes earlier. She calmed me down. I looked at the airline’s website and saw that it had a navigation tool to follow planes. I sat in my office and watched Flight PS752 take off on time. I followed the little dot all the way to the border. I felt such relief when it crossed out of Iranian territory.

I didn’t realize that the navigation tool was charting the flight path their plane was supposed to take, not the actual plane. That night, in my blissful ignorance, I walked away from my computer. I washed the dishes. I cleaned the floor. I double-checked that Parisa’s car was filled with gas for her first day back at work. The only thing I had left to do was buy flowers for them.

Then I looked at my phone. I saw eight missed calls from Iran. That’s when I learned the news that destroyed my life. A few minutes after takeoff, Flight PS752 had crashed into the ground and exploded southwest of Tehran with 176 passengers and crew on board. There were no survivors. We have a saying in Farsi: there is no colour after darkness. I never speak about that first hour in the darkness. I’ve shared much of my story with the world, but that first hour belongs to me.

That night, friends found me standing outside of our house, shivering in a T-shirt and shorts. They booked my ticket to Iran immediately. I needed to bury the bodies of my wife and daughter. I needed answers. At Pearson airport, a man in front of me in the security line-up was crying. He was too distraught to organize his belongings to get through the scanner. I asked him whom he had lost, and he said his son and wife. I told him that we should not let them break us. He asked me whom I meant by “them,” and I said, “The regime.”

As we flew to Frankfurt for our connecting flight, the attendant sat with me and cried. On my next flight, to Tehran, five of the passengers had lost 10 people in the downing of PS752. We were flying over Turkey when the pilot announced that we could not land in Tehran for security reasons. American officials had just declared that PS752 had been felled by a missile strike from Iran. We returned to Germany. I didn’t arrive in Iran until the next day. Three lawyers I met on my flight told me that they would intervene if I had problems at passport control, but I got through with no trouble. With that, I entered the last building my loved ones had been in before they were murdered.

I fell into the arms of our mothers and Parisa’s sister. Already, DNA from Parisa’s grandparents had been used to identify her body; my parents’ DNA was used to identify Reera’s. That night, in my mother-in-law’s home, I imagined my wife and daughter packing their suitcases, adjusting items to make room for Reera’s new books and dolls. Sometime between their departure from this room and my arrival, their lives had ended and, in effect, so had mine.

I’ve shared much of my story with the world. But the first hour after my wife and daughter died belongs to me

A painting of Parisa and Reera

That night, under mounting international pressure, the Iranian government released a shameful statement acknowledging that it had shot down the plane. The regime offered no explanation. As details emerged about Iran’s culpability, I changed my mind about burying my family in the country and instead insisted on bringing them home to Canada. I demanded to see their bodies. Everyone told me not to, but I needed to bear witness. They were being held in a morgue and had already been placed into coffins, which were wrapped in the flag of the Islamic republic and piled six high. Writing on them identified the remains. I found one marked “Martyr Parisa Eghbalian.” Another, marked “Martyr Reera Esmaeilion,” was higher up. My daughter’s coffin, I assumed, was lighter than most of the others. The regime was trying to present their deaths as an act of loyalty. Representatives from the Islamic republic came to my parents’ place to install a banner with a congratulatory message about Parisa and Reera being Iranian martyrs. We refused. At a memorial that Parisa’s grandfather held for her and Reera, the IRGC hijacked the service and put its representatives behind the podium.

The regime still won’t admit the full horror of what it did. We now know that Parisa and Reera’s plane was the tenth to fly out of the Tehran airport that morning. It was functioning perfectly. The flight did not deviate from the pre-approved course that I’d followed online. Its takeoff, at 6:12 a.m., was delayed but otherwise normal. One minute later, the operator of an Iranian surface-to-air missile system categorized the passenger jet as a threat. At 6:14 a.m., the operator fired a missile at the plane. The pilot appears to have made an effort to turn the plane around. About 30 seconds later, an operator fired a second missile. A fire broke out on board before the plane hit the ground and exploded. Later that afternoon, the Iranian government bulldozed the crash site like it wanted to erase my wife, my daughter, 174 other people and the plane that had carried them from history.

I fought hard to bring my wife and daughter home. The transport company said that there was no room on my flight. There was a backlog because of the number of flights cancelled in Iran after the crash. I travelled with my parents and Parisa’s mother. Our moms were so devastated that they couldn’t stand, so we pushed them in wheelchairs. As our flight took off out of Tehran, I counted, the same way I had always counted with Reera, who was afraid of flying: one, two, three... Three minutes after takeoff, I looked out at how high our plane was. This is how high they were when they were shot out of the sky. The next day, Parisa’s and Reera’s bodies followed me to Canada. They are buried in Elgin Mills Cemetery, under a monument called Winter that depicts three broken trees. This is an eternal winter for us. After this February comes another February, then another February.

Two months after the crash, the other families and I formed the Association of Families of Flight 752 Victims. We wanted to be united in our grief, to keep the memories of our loved ones alive, and to seek justice and answers. I’ve never been silent about the regime, and now I’m joined by hundreds, supported by thousands. We don’t want an apology. We don’t want compensation. We want the truth. We want the culprits, the perpetrators and commanders of this atrocious crime, to be identified and brought before the International Criminal Court.

After the crash, the IRGC mixed up the victims’ remains and failed to do proper DNA tests. Their belongings were looted. Their luggage, their passports—everything was gone. The only things I got back were a cellphone and the key to our house in Richmond Hill. Eight months later, the RCMP gave me Parisa’s Apple Watch. I can turn it on, but it doesn’t give me any information about the three minutes and 42 seconds that they were in the air. I would like to know everything she did and felt in that time. One day, while I was walking in Toronto, a stranger stopped me on the street. She recognized me from a TV interview and said she had Reera’s OHIP card. It had been given to the wrong family. I keep it in my bookshelf, alongside Parisa’s dentistry textbooks. I have my wife’s OHIP card now too, also returned to me by a stranger, who messaged me on Instagram.

I cried constantly the first year after their deaths. On Reera’s tenth birthday, I wrote her a letter. “I am deeply sorry, my sweet little girl, that the future for you, your mom, and for me turned into cold ashes.” After two years, all I wanted to do was die. I kept telling myself that I needed to survive so that people would know the injustice inflicted upon my family and so many others.

So many people complained about being confined to their homes during Covid. Confinement is more tolerable than devastation. Some of my family came to stay with me because life had become unbearable for them in Iran. At night, no one could sleep in our house; you could hear people crying in their rooms. The door to Reera’s room remains closed, her wrapped Christmas presents inside. No one goes in there. I see her monkey bars folded in the closet, still waiting for her to return. I’ve cut my hair short and grown a beard; Parisa did not like it this way. But no one who is alive cares what my hair looks like. I smoke now.

Esmaeilion and other members of the Association of Families of Flight 752 Victims organized huge protests in Toronto (top) and Berlin (below)

Esmaeilion and other members of the Association of Families of Flight 752 Victims organized huge protests in Toronto (left) and Berlin (below)

In September, I sat at my computer, stunned by the news coming via Facebook from Iran: the morality police had detained 22-year-old Mahsa Amini after deciding that she was wearing her hijab inappropriately, allegedly showing too much of her hair. She fell into a coma while in police custody and died three days later at a hospital in Tehran. Authorities claimed that she had died of heart failure, but no one believes that. This is a murderous regime. Her father says that she had no pre-existing medical conditions. When he finally saw her body, there were bruises on her legs. He believes that she was beaten to death.

Mahsa Amini was around the same age that Parisa—who had always bent the clothing rules—was when we got engaged. What happened to Amini resonated with me and with people everywhere. It added new heat to long-simmering anger. It’s like we lost our loved ones again. Iran has erupted in protests. People are fed up with the violence. They are tired of suffering. They are tired of murder, incompetence and fear. They are tired of women being denied an experience as basic as feeling the wind rushing through their hair. They are so angry that they are willing to risk their lives. They want to be free.

Like many, I worry about the risk of violence in Iran. That’s why I continue to protest. We’re fighting against our country’s injustice and calling for change, for democracy. We’re keeping the world’s eyes on Iran. Since Amini’s death, my team and I have organized protests in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, Ottawa and other cities across Canada. I spoke at a United Nations protest in New York. I worked with a team of activists to put together a rally in Berlin, where 100,000 people showed up. My phone goes off every minute, a hundred messages an hour from people in Iran, families in the association, reporters.

This is a revolution. Everybody knows that. It is not unrest. I cannot let my grief isolate me. I must show up for myself, for the other families and for the Iranian people. We want the Canadian government to ban high-ranking members of the IRGC from Canada and to increase sanctions against powerful, wealthy Iranians—similar to the sanctions we’ve seen recently against Russian oligarchs. We want an investigation by the International Civil Aviation Organization into Flight PS752. We want the IRGC declared a terrorist organization.

Some people have told me that I am going too far, that I should stay out of a fight with the regime, that this fight will destroy me. But it is too late for that. I have lost everything. I live in the darkness. Like many others in the Iranian diaspora, I try to echo the voices of the voiceless. Recently, I watched a video of a teenager in Sari, Parisa’s hometown. She ripped off her headscarf, danced with it and then tossed the garment into a fire. I knew that this is what Parisa would have wanted to see: Iranians fighting for their freedom. And, in that moment, my heart broke all over again.

This story appears in the December 2022 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here.