By John Semley

January 19, 2023

50 years after it all started

Untold stories from second city, the group that changed comedy

An oral history featuring:

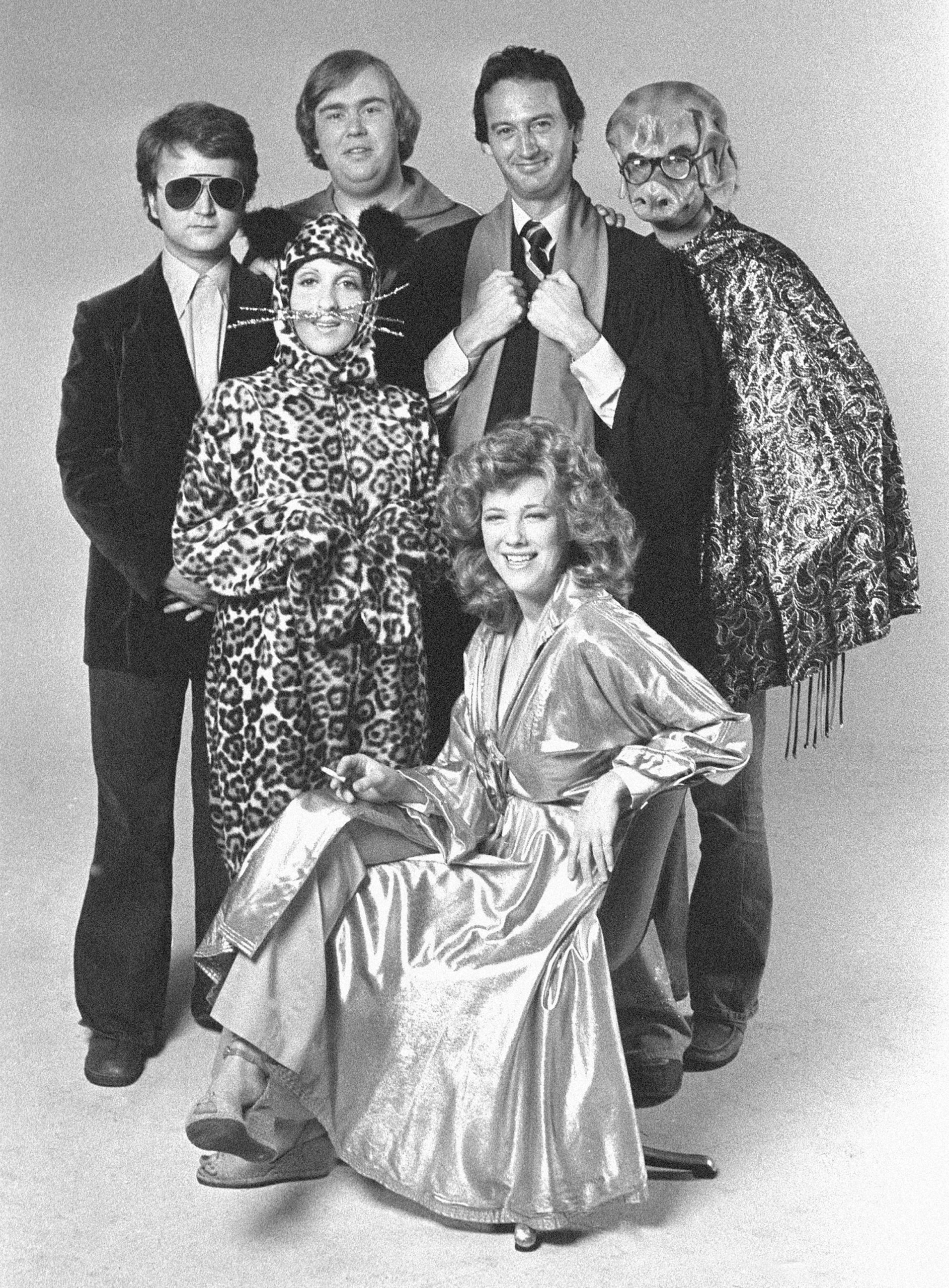

When Second City—the venerable Chicago theatre company known for crafting live, long-form comic improvisations—arrived in Toronto in 1973, it was a fun, fresh voice in a comedic landscape that seemed stale, parochial and wholly underdeveloped. Second City buzzed with a liberating, free-form energy. And it drew in a group of friends, a rotating cast of actors and students who thrilled at making one another laugh.

Across various stages and performance spaces, Second City Toronto catalyzed a Big Bang of Canadian comic talent. It nurtured performers whose wit and chummy faces would dominate the comedy landscape, on both sides of the border, for decades to come: John Candy, Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Joe Flaherty, Dave Thomas, Dan Aykroyd, Andrea Martin, Robin Duke, Gilda Radner and many others.

The early years were loose and chaotic—a gaggle of young nobodies busting into local pubs and corralling patrons into dingy theatres to watch their shows. Some audiences got it. Some didn’t. One angry early patron reportedly hurled a highball at the stage and was swiftly ejected by a police officer (really just an improviser in a cop costume). It all had a rickety, unvarnished, fly-by-the-seat-of-the-pants quality that would best be described as, well, improvisational.

In the 50 years between Second City Toronto’s opening on Adelaide Street East and its recent move to a theatrical megaplex at One York Street, its star-studded cast changed comedy, won back-to-back Emmys for their spin-off television series SCTV and cemented Toronto’s image as a comedy capital. To mark Second City Toronto’s 50th anniversary, we spoke to early cast members about the troupe’s first decade and how it helped shape a fresh, silly and distinctly Torontonian comic sensibility.

By the time it made its northward expansion, Second City was the buzziest thing in comedy. Why Toronto?

“MARTY SHORT HAS SAID THAT, TO HIM, TORONTO IN THE MID-’70S WAS LIKE PARIS IN THE 1920S”

—DAVE THOMAS

Joe Flaherty: The co-founder and producer of Second City Chicago, Bernie Sahlins, announced that he wanted to open up a second theatre, in Toronto. Like most Americans, our cast in Chicago didn’t know anything about Toronto. Nobody was interested in coming up except me and Brian Doyle-Murray. We volunteered. I was looking for something different, and I thought it might be fun. Toronto was on the verge of becoming—what does it love to call itself?—world class.

Robin Duke: Toronto was coming alive. It was a renaissance. I was in university at the time. You could go out at night to cool restaurants where young people were eating hamburgers in a fancy place!

Dave Thomas: Marty Short has said that, to him, Toronto in the mid-’70s was like Paris in the 1920s—a place where artists and comedians congregated. It sounds like braggadocio, but I don’t think it is.

Martin Short: I think the analogy is accurate.

Rick Moranis: Are you sure Marty didn’t mean Paris, Ontario?

Joe Flaherty: We held auditions for the original cast at a little church in Yorkville. We were shocked at how good people were. We got our first show underway at an old photography studio on Adelaide Street that Bernie had turned into a nice little theatre space. But he made two big mistakes. First, it didn’t have air conditioning, and we opened up in late June. Second, he didn’t get a liquor licence, which for cabaret was essential. If you had a minimum drink deal, everyone in the audience was guaranteed to enjoy themselves. We had a good show and a great cast, but we barely got anybody to watch. We’d have audiences of 10 or 12 people.

Catherine O’Hara: Brian would rant to the audience about how hot it was. There may have been no liquor licence, but there was definitely some smuggling going on.

Martin Short: Lots of those early cast members were my friends. We had all done a production of Godspell together: me, Eugene Levy, Gerry Salsberg, Jayne Eastwood and Andrea Martin. I was drawn to the kind of comedy they were doing as opposed to stand-up. I thought it was fantastic. I remember Joe and Brian did a sketch about a student faking his way through an oral Russian history exam. It was brilliant.

Dave Thomas: Joe was the professor and Brian was the student. Those two guys were really, really good.

Catherine O’Hara: It was wild comedy for thrill seekers. There was tension—an exciting tension—underneath everything. “Where is that going?” And it was the ’70s. You could be looser and freer. The audiences were cooler. I remember the new-wave band Rough Trade would come in when they weren’t playing a show to watch the improvs.

Dave Thomas: Comedy was in a transition period. The set-up/punchline gags of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In and The Wayne and Shuster Hour felt old to us. At Second City, the cast members were writing the sketches live on stage. And they were doing stuff that was really funny. That was the thing that attracted us all.

Catherine O’Hara: I auditioned for Godspell along with my sister Mary Margaret. We got a callback, but we didn’t get the parts. So we took jobs waitressing at Second City just to be able to watch the cast perform every night.

Dave Thomas: Eugene, my friend from our college days at McMaster, invited me to audition for Second City. I had to do improv sets with the cast for an entire week, Monday through Thursday. It was exhausting. I was just this third wheel trying desperately to be funny. But I got lucky and got in. Then I had to tell my bosses in advertising that I was quitting. They thought it was about money. They said, “Well, how much will you make?” I said, “$145 a week.” I was making $70,000 a year and on track to be a creative director. They thought I was insane, but I never looked back.

That first space on Adelaide Street shut down after a matter of months. What happened next?

Catherine O’Hara: Bernie Sahlins returned to Chicago to run the Second City there, and an English theatre producer, Andrew Alexander, took over Toronto. He moved us to the Old Firehall on Lombard Street. I auditioned, and John Candy, God bless him, put me in the touring company, which he was directing. Then Joe took me on as Gilda Radner’s understudy. I got on the main stage when Gilda left to do The National Lampoon Radio Hour.

Robin Duke: Catherine was my best friend from high school. I watched her and the rest of the cast being smart, funny and irreverent and doing all these fun characters on stage. I thought, This is what I want to do. So I started taking improvisation workshops. The rooms reeked of beer and smoke. One day, I walked into comedy director Del Close’s workshop and he said, “Okay, you’re in.” It turned out he was choosing people for the touring company. He just picked the first seven who walked through the door! I am so friggin’ lucky.

Joe Flaherty: At the time, Marty was doing musical numbers with his wife, Nancy, in a room upstairs. He didn’t join our cast until later on, but he used to throw great parties and invite everybody.

Martin Short: I waited so long to audition because I was afraid. The idea of improvising comedy was daunting to me. I liked doing musicals and plays. I always saw myself more as an actor than as someone in comedy. I joined in 1977, when I replaced John Candy in a show. Instead of playing a scene like John played it, it was like, “Why don’t I just do it as, oh…Columbo?” They wanted you to play to your strengths.

Catherine O’Hara: It was my university of comedy: writing, character development, thinking on your feet and learning about scene structure. All of the lessons I learned there, I’m still working on every day. They threw out a lot of references in Chicago. They loved to drop philosophers’ names. Or authors’. In Toronto, we were just trying to crack people up. For us, it was about characters: people we met on the subway, our family members. Our scenes were more about the dynamics between human beings. It was more emotional. We weren’t as well read.

Joe Flaherty: We were just trying to be funny! Get laughs! In order for the audience to accept us, I wanted them to leave the theatre having laughed a lot.

Dave Thomas: Bernie Sahlins was originally an accountant. So he wasn’t exactly Mr. Comedy. He never really made me laugh. At least not intentionally. And Del Close was funny, but he was also insane and dysfunctional. He’s been lionized in death way beyond his practical usefulness in life.

Martin Short: Chicago was more high-minded. In Toronto, the audience was laughing harder. It was real character work. You’d have Catherine and Robin playing two drunken truckers trying to stay up late. It was just funny.

Catherine O’Hara: I basically played people who couldn’t think straight. That would be my excuse for sounding like I didn’t know what I was talking about.

Robin Duke: Improvising with one another was the best feeling in the world. John Candy loved the stage so much that you couldn’t get him off it. The stage manager would turn the lights off on a scene, then the lights would come back up and John would still be there, trying to finish the sketch.

Catherine O’Hara: John was the king of “Yes, and…” on stage and on the street. We’d be at the mall and people would come up to him and try to do bits with him. He would jump right in with anybody and everybody.

When the cast wasn’t training, touring or performing, you all hung out at The 505, a not-quite-legal boozecan on Queen Street East run by Dan Aykroyd and Marcus O’Hara, Catherine’s brother.

“it was my university of comedy”

—Catherine O’Hara

Catherine O’Hara: Last call was the same time that our shows were ending, so there was nowhere for us to drink. A bunch of theatre people gave them money to get it started. My sister and I would go there after waitressing, fall asleep in the barber chairs they had and stay overnight. It got bigger and bigger—the police were watching it all the time. It was a storefront. A completely wide-open storefront. It was so conspicuous that it was inconspicuous. Like, “There’s no way something illegal is going on there! Look at that big window!”

Dave Thomas: Dan had an interesting cross-section of buddies. A lot of them were cops, and they would come in and have a beer. And he was good friends with Wally High, who was one of the guys in Satan’s Choice, the motorcycle gang. It was like, “How am I, an English major from McMaster University, going to become friends with a member of Satan’s Choice?”

Robin Duke: When the Chicago cast would come up, they’d all be there: John Belushi, Bill Murray. Everybody went through The 505. If the police had ever shut it down, you wouldn’t have the comedy you have today. Everybody would have been in jail.

Martin Short: I remember being there once and boring Robert Klein, the American stand-up comedian. I was trying to explain to him why I thought he packaged comedy brilliantly. He said, “This is an interesting lamp” and got up and left.

Dave Thomas: It was not a club at all. It was a small dumpy house with a completely disgusting toilet downstairs. You had to have a strong stomach to go down there.

Flaherty via Facebook, other headshots by Getty Images; archival photos courtesy of The Second City, Inc.

When Lorne Michaels launched Saturday Night Live in 1975, he stacked the original cast with talent from Second City Toronto. Did the Canadian crowd take that as a compliment or a slight?

Martin Short: The first person Lorne cast for SNL was Gilda, followed by Dan.

Dave Thomas: There was a little bit of jealousy. SNL became a sensation so fast. I mean, Danny was in Second City with me when I started. We were working on a screenplay together. So, when he went to do SNL, I lost a writing partner. I was kind of bummed. Joe, in particular, was bothered that we didn’t have the acclaim and fame that SNL had. That was haunting him. He’d trained Gilda and other cast members from Chicago, like John Belushi. I think a part of him always wished that he was on SNL.

Catherine O’Hara: The whole thing inspired Andrew Alexander to start SCTV. “Wait a minute—why are they going somewhere else? We could do it here!”

Joe Flaherty: Andrew and Bernie called me into a meeting with one of the executives from Global Television Network. They said, “We want to do a TV show because Saturday Night’s getting all of our people.” We were going to go into competition with SNL? On Global?!

SCTV premiered on a handful of stations in Ontario in 1976. The show was initially produced on the cheap and followed the inner workings of a rinky-dink TV station in a fictional town called Melonville. How did you land on the concept?

Joe Flaherty: I think Del Close came up with the idea that we’d be running a fictional television station. We weren’t interested in being hip or cutting edge. We just wanted to be funny and make fun of TV. I hand-picked the cast—me, Eugene, Catherine, John, Dave and Andrea. And I had loved working with Harold Ramis at Second City in Chicago. Smart guy. Really funny. I thought he’d be really valuable. He agreed to come up, join the cast and help write sketches for the show in Toronto.

Dave Thomas: Harold embraced the cheapness of SCTV. Eugene, Catherine and I were always moaning about how bad the sets looked and how shitty the props were. Harold would just chuckle and go, “That’s part of the charm!” We had a difficult transition from stage to television in the first season. Bernie wanted us to do plays. He wanted us to do Sartre and Chekhov and parodies of those things. And we were like, “What the hell is that? Our audience is a television audience!”

Catherine O’Hara: We just brought whatever lessons we’d learned. There was no improvising a whole scene. So, for the first time for most of us, we were actually writing the scenes down on paper. Since we didn’t have a live audience, we couldn’t know what anyone else thought about the scenes. It was really about trusting one another as our gauges of what would work and not work and finding our voices.

Robin Duke: It was just people having fun and making one another laugh. It was such a community in that way: the love of the process and of creating these funny scenes. You had far more creative freedom on SCTV than you did on SNL, which I joined in the ’80s.

Joe Flaherty: We didn’t have to answer to anybody. And there was no backbiting or trying to one-up one another.

Catherine O’Hara: We were trying to make one another laugh, for sure. When people you respect like your work, that’s the best.

Joe Flaherty: When SCTV first went on air, nobody was watching it or talking about it. I think our first review for the show was in High Times, a magazine for stoners. But we were pretty straight, across the board. Nobody did drugs on our show.

Dave Thomas: We all worried. We thought, Shit, is this going to go anywhere? But we loved what we were doing even though we were making piss-poor money.

Joe Flaherty: Marty was a big fan of the show. He was one of our earliest supporters. He really boosted our egos by watching SCTV and telling us how much he loved it.

Dave Thomas: When Chevy Chase left the original SNL cast, Joe, John and I auditioned for the open slot. Lorne came into town acting like a little prince. It was a painful audition. We did what was probably the worst improv of our lives. Bill Murray got the part. Afterward, Lorne told John Candy not to give up his day job. It was a joke, but John never forgot that. By SCTV’s second season, the sense of competition with SNL had disappeared because they’d become so big. We were only getting smaller—stations started dropping us. People were discouraged, but we kept filming. Things turned around once we made it to American networks. By the ’80s, we were airing on NBC.

It must have been freeing to stop comparing yourselves to SNL. SCTV leaned in to being its own offbeat, culture-defining show, with old buddies coming and going.

“The lunatics were running the asylum”

—Rick Moranis

Rick Moranis: Some original cast members were leaving for new opportunities. I was working in radio in Toronto and doing some stand-up and comedy writing. I hadn’t come up through Second City, but Dave Thomas had seen an impression of Woody Allen that I’d done. A while after that, he invited me to lunch and asked if I was interested in doing the show. When I joined SCTV, in 1980, he was the head writer. He created this rule that, if your sketch was two minutes or under, you could do whatever you wanted.

Dave Thomas: One of the things I’d learned from advertising is that you can say a lot in 30 seconds. That’s the essence of television, especially in sketch comedy writing.

Martin Short: I was an interloper. I joined in 1982, when SCTV was already the hippest show on TV. If I was doing a piece by myself—like Ed Grimley being hypnotized by a snake—Dave might walk by and say, “I don’t know what you’re doing, but keep doing it.”

Rick Moranis: The lunatics were running the asylum. Some of the biggest laughs at the writing table and read-throughs were when nobody thought an idea was funny and it just died terribly.

SCTV was beloved for its extended parodies and satires as well as its celebrity impersonations: Eugene Levy as a barely breathing Perry Como or Dave Thomas as Liberace. I imagine not everyone you skewered took kindly to it.

Dave Thomas: There was a biopic of Liberace being made about a decade after SCTV. I got a call from someone who worked for him. He was livid, saying, “Who the hell do you think you are, doing that tasteless impersonation of Lee? We want a retraction—and take it off the air immediately!”

I said to him, “I can’t do a retraction because it’s been on air in syndication for years. So you’re a little late.” How did he even see this? Turns out my agent had sent him the tape, submitting me for the role. They thought this was a genuine audition piece! I called my agent up and said, “Are you out of your mind?!”

Rick Moranis: I was a big George Carlin fan. How could I not be? But there came a point where I saw him on a talk show, and he was reading off cards. I had a feeling I could look like him, so I did an impression of him reading off notes and telling lazy jokes. Years went by and I was at an awards show. Across the aisle was Carlin, sitting there. We looked at each other, and he just said, “Brutal. Brutal, man. Brutal.” I sort of shrugged and gestured about how much I love him. But I never really met him. Years later, after he passed away, I spoke to his daughter, Kelly. She wanted to use the SCTV clips in a show she was putting together. I told her, “Look, I want you to understand that, believe it or not, that was really done out of reverence.” She said, “No, you don’t understand. It had a profound effect on him. He wasn’t aware that he was really being lazy. He was unhappy and wasn’t doing the kind of work that he wanted to be doing. And your impression caused him to change his approach.” God, am I glad I spoke to her.

SCTV gained a cult following, after its cancellation in 1984, thanks to a steady flow of syndicated reruns. Nearly four decades later, much of the original cast is still dominating comedy. Did you ever expect to leave such a legacy?

“Everyone from SNL wanted to do our show”

—Joe Flaherty

Joe Flaherty: SCTV could have gone on. But it was cancelled. By our last season, in 1984, the whole comedy crowd—all the people from SNL—wanted to do our show! It was our baby. We watched it grow and even won two Emmys. It was a great experience, and I’m sorry it ended. I could have done Second City for the rest of my life.

Rick Moranis: Why don’t things that end up getting cult status reach the mainstream? Is it because they were never going to appeal to everybody? Or could it be for other reasons, maybe ones related to marketing? I mean, who was going to see us perform when we were on from 12:30 a.m. to 2 a.m.? It took a long time for people to catch up with us.

Dave Thomas: In 1999, SCTV was honoured at the US Comedy Arts Festival. Conan O’Brien, the moderator, said that he and his brothers used to watch SCTV, and because of how obscure the show was, Conan had gotten the feeling that it was just for him. The Simpsons writers will tell you that they grew up on SCTV and modelled their work after it. People have a very personal attachment to it.

Martin Short: It’s brilliant work that is still funny today. Martin Scorsese is doing a documentary on SCTV, and we did an event a few years ago in Toronto. Little pieces were played, and the audience was laughing like they had been made yesterday.

Catherine O’Hara: I know how fortunate I am to have somehow been associated with those lovely, funny people all those years ago. And to still be able to work with them and learn from them. To keep getting to be silly and funny at my age is great.

Dave Thomas: My niece recently said to me, “I graduated from Second City and now I’m certified funny!” That’s not what Second City should be. When I joined, it wasn’t a stepping stone. You auditioned, and if you didn’t get in, you were in the audience. You’ve just got to jump in, and you either sink or swim. Am I just sounding like an old guy now?

These interviews have been edited and condensed.

This story appears in the February 2023 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here