white

lies

after my dad died, I found a new family in a white-power gang.

I spent years dressing like

a skinhead, fighting strangers

and committing petty crimes

before I realized the absurdity

of my beliefs.

Inside the twisted world of Toronto’s white supremacist movement

By Lauren Manning

portrait By

Markian Lozowchuk

i grew up in Whitby, a town so homogeneous that people called it “White-by.”

My mom, Jeanette, worked in land surveying, and my dad, Paul, was a detective constable with the Toronto Police Service who went after sexual predators and dealt with at-risk youth. They were loving and protective of my younger brother and me, keeping us away from kids they thought would be a bad influence and enforcing a strict routine: wake up, go to school, come home, do homework, go to bed. Once, when I got home five minutes late, my dad lost his mind: “I thought you’d been kidnapped!” I was too young to realize that his concern stemmed from his work.

Growing up, I wasn’t comfortable in my own skin. I woke up many mornings wanting to be someone else. The summer I turned 14, my parents enrolled me in a week-long music camp. I knew immediately that I didn’t fit in. Most kids played guitar, bass or drums and dressed the rock ’n’ roll part—ripped jeans, band T-shirts, dyed hair. I played clarinet and wore track pants and baggy T-shirts, my hair pin-straight and short like a boy’s. I was confused about my sexuality, which made me feel lost and alone. Over the course of the summer, I gained a few pounds, which made my already fragile self-esteem even more brittle. I felt ugly and fat and wanted to hide. I struggled academically. It was hard to communicate why, so I would throw my hands up and say, “I’m stupid!” My parents tried to tell me it wasn’t so, but no one could convince me otherwise.

In 2006, when I was 16, my dad found out he had acute myeloid leukemia. I was devastated. He was my best friend, always around, always encouraging. He’d taken a special interest in my woodworking class, enthusing about everything I’d made. It was weird not having him at home. After two months of chemotherapy at Princess Margaret Hospital, he looked like a skeleton, his sagging flesh hanging off his bones. By the end of the year, he’d fallen into a coma. The last time I saw him was on a Saturday night in January of 2007, hours before he died. His death left a deep void inside me. It took a long time for me to accept that he was gone.

Punk rock and metal became my safe haven. The loud, aggressive, I-want-to-beat-someone-up sound left me feeling euphoric, and the lyrics assured me that outcasts like me mattered. With my headphones on, I could block out whatever was going on in my mind. I started hanging out with metalheads at school and drinking heavily. I couldn’t see the point of life when I was sober.

That November, I was on the Facebook page of Nokturnal Mortum, a metal band I liked, when I received a message from a 26-year-old guy from Toronto. I’ll call him Donny. “I was wondering if you’re NS or just listening to NSBM?” he wrote. I didn’t know what he meant, but I soon learned that NSBM stood for National Socialist black metal. Nokturnal Mortum’s growling lyrics, although hard to understand, were filled with messages of white supremacy. They spoke of taking back land that, in their view, rightfully belong to them. When Donny asked me what other bands I liked, I gave him a list, not realizing that some of them were racist. I didn’t ask what “being NS” meant because I didn’t want to sound stupid. I just enjoyed having someone to talk to.

A few days later, Donny messaged me again to tell me that a friend of his in Ottawa had been beaten up by a couple of Black guys. “This is how us white people get treated,” he wrote. “And Blacks get away with this shit.” I wasn’t exactly sure what Donny meant, but it sounded a lot like what my grandfather used to say. Poppa disliked all visible minorities as well as Jewish and LGBTQ people. When Donny repeated that rhetoric, it seemed familiar, and I believed it. Still, I didn’t know how to respond, so I changed the subject, writing about the preppy kids at school, whom I couldn’t stand. When Donny called them “a bunch of mainstream sheep,” I laughed. The label fit so well. I liked the way Donny spoke to me, as though he’d known me forever. “You’re smarter than everyone else around you,” he said. “The world needs more girls like you.” He made me feel like I mattered.

Over the next month, Donny began referring to “the movement.” He said that Jews controlled the world, that Black people were trying to get back at white people for slavery, and that the education system was trying to instill a sense of shame and guilt in white kids just for being white. He said he was part of a resistance movement fighting to ensure that the white population survived. The movement had “crews” that could be identified by symbols: Dr. Martens boots with white laces, specific tattoos and coded language. He told me about Stormfront, a white nationalist, neo-Nazi internet forum, and I created an account, “educating” myself about how white liberals were being brainwashed. This new knowledge made me feel like I was better than everyone else.

I first met Donny in person in December, when he came out to Whitby by train. I thought he was cool, and his crew, which I thought of as a secret club, sounded more interesting than hanging around drinking with my classmates. So, when he invited me to join, I said yes. Later that month, I skipped school to sneak off to Toronto and meet the crew. There were about 10 of them, mostly guys in their late teens and 20s, and they called themselves SD, from the German word Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence and security division of the German SS and Nazi Party. I marvelled at how they seemed to have one another’s backs. They accepted me without question. With them, I found a sense of family I’d been missing at home. My mom had always been closer to my brother. She and I fought all the time: about my grades, my attitude, the rhetoric I had increasingly been dropping into conversation. Without my dad’s friendship and love, I felt I didn’t have a place in my own family.

I wish I had known how misguided my thinking was, how dangerous it was to cast my lot with Donny and his crew. Their beliefs were toxic, harmful and totally divorced from reality. But I was angry, hurt and rebellious, and Donny showed me where to direct my rage. He took me to Holocaust denier presentations and walked me through ethnically diverse neighbourhoods near Bathurst and St. Clair. “We’re being wiped out,” he told me as we passed the homes of brown-skinned families. I believed everything Donny said and began defining myself as a white-power skinhead. I liked the sense of importance that came with belonging to a group fighting for a cause, something I’d never felt before.

That spring, Donny gave me a set of Panzer boots. They were steel-toed with white laces, tangible proof that I was part of the movement. On June 22, just days after I graduated from high school, my mom gave me an ultimatum: either I start behaving like I wanted to be part of the family, giving up Donny and everything he’d taught me, or she’d throw me out. “You decide,” she said. “Who’s more important to you: your family or your friends?” It was an easy choice.

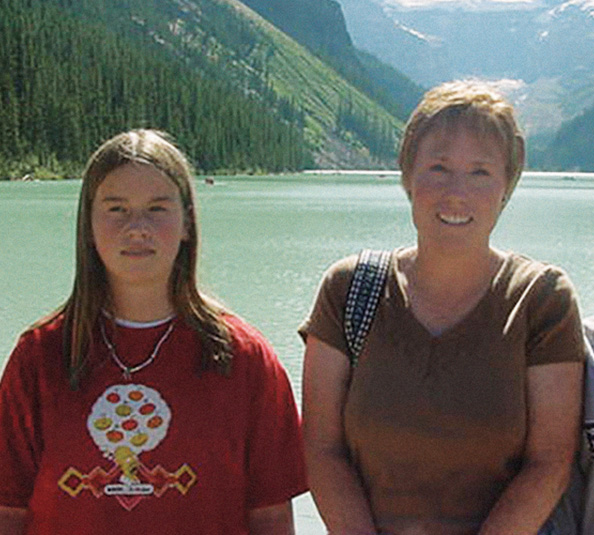

Clockwise from top left: the author with her late father, Paul; at age 15; vacationing at Lake Louise with her mother, Jeanette

AFTER LEAVING HOME,

I took the GO Train into Toronto and met up with Donny. Initially, I slept on the floor in the basement of an internet café at Yonge and Bloor, and then I moved to the Palace Arms, a cheap now-defunct rooming house at King and Strachan. Donny used stolen and fabricated credit cards to buy stuff. I got a job at a grocery store and, later, washed dishes at a ’50s-style diner. It wasn’t great, but at least we were free to hang out with our crew after work.

Members came and went, but Donny and I were in it for the long haul. Though we weren’t in a romantic relationship, we spent all our time together. He taught me how to armbar, hip throw and hit with force, then made me the group’s enforcer. We’d get into street fights with anyone who gave us trouble. All it took was for someone to yell “Nazi scum” and we’d start brawling. We spent a lot of time partying in the forested areas around High Park and Old Mill, pretending to be Vikings, setting up bonfires and drinking. I spoke at crew meetings, using aggressive, over-the-top language to keep the guys’ interest. They listened to me and seemed to respect me. I felt validated, powerful and smart. After years of feeling invisible, I felt seen.

I wanted to prove that I was committed to the movement, so I shaved the left side of my head and got “1488” tattooed on my neck: “14” for a notorious white-supremacist phrase called the 14 Words (“We must secure the existence of our race and a future for white children”) and “88” for Heil Hitler, or HH, H being the eighth letter of the alphabet. I thought that, if I wore this angry mask, adopted this badass persona, everyone would be afraid of me and no one could harm me.

Three weeks after I left home, a police officer from Durham visited me at the Palace Arms. My mom had asked him to check up on me. She’d been distraught since I left, sending me emails offering to work things out. At one point, I agreed to move back home, but when I failed to follow her rules—observing a curfew, cutting contact with the movement—she kicked me out a second time. After that, I decided I’d never speak to her again.

One night, Donny disappeared without saying where he was going. I didn’t make much of it until he showed up the next morning. His eyes went wide as he grinned. “I broke into your mom’s place,” he said, wound up with excitement. Then he showed me my mom’s Mastercard. “Get showered and make yourself look good. We’re going shopping.”

The back of my neck was tingling, a sign that something bad was happening. I thought about walking away but realized that I wasn’t in any position to argue. Donny, who could sense my hesitation, knew it too. “You’re homeless. You’ve got nowhere else to go,” he said. “Get dressed.” Donny bought me a fake ID bearing my mom’s name and my picture, and we went to a Future Shop in North York, where we bought a MacBook and an HP printer. The charge: $2,858.86.

Over the years, I’d learned to ignore stuff I didn’t want to deal with and block emotions that might make me vulnerable. Still, I wanted reassurance. “Should we have done that? Ripped off my mom?” I asked. “She deserved it,” Donny replied.

A little later, Donny introduced me to Paul Fromm, a former teacher with ties to the Ku Klux Klan. He had founded the Canadian Association for Free Expression, which advocates for racists, antisemites and Holocaust deniers who are being prosecuted for hate crimes. His handshake was firm, and he took a special interest in me. “It’s refreshing to meet a young lady who isn’t brainwashed by MTV culture,” he said. Fromm was impressed by my dedication to the movement. He asked me and my crew to pass out flyers at his speeches and put pamphlets beneath doors in west-end apartment buildings.

As the weeks wore on, Donny and I started bickering. He could be funny and had initially seemed like an older brother or father figure. But, when he started picking fights with guys he called “Listo-bums”—people who drank Listerine to get drunk—I began to see that he wasn’t the person I’d thought he was. One afternoon, a homeless Indigenous man overdosed in front of me, his face going colourless. I called 911 and stayed with him until first responders arrived. Despite my racist rants, somewhere deep down I knew that this was how you were supposed to treat another human being. This guy needed my help, no matter his ethnicity. But Donny showed no empathy, and I began to wonder if he had his head screwed on right. I didn’t find him or his antics funny anymore, so I wasn’t upset when, one evening in late October 2008, he abruptly took off for BC, saying he was sick of Ontario. He sent an endless stream of emails asking me to join him, then called one day threatening to kill himself if I didn’t come. I could tell that he was trying to manipulate me, plus I had a good job at the diner that I didn’t want to give up. When he called the next day to tell me he hadn’t done it, I finally told him I’d had enough.

With Donny gone,

our crew dissolved, and I went looking for a new one. At the time, there were a handful of white-power groups operating in and around Toronto. Online, I’d met a girl who was part of Aryan Nations, a decentralized white supremacist network that had grown out of Idaho. Through Donny, I also knew two members of Combat 18, a violent neo-Nazi group that Canada added to its list of terrorist organizations in 2019. And everyone in the movement knew the Vinland Hammerskins, probably the biggest and most organized group in the city. It had members in Scarborough, Etobicoke and Mississauga, distinguishable by the dual-hammer patches on their jackets. Founded in Texas in the late 1980s, the Hammerskins hosted white-power concerts, preached traditional family values and flirted with the idea of building their own all-white community.

About a month after Donny left, I met a guy loosely associated with Blood and Honour, a UK-based coalition of skinhead gangs that was prominent in BC. He walked into the diner during one of my afternoon shifts, wearing black boots with white laces, so I introduced myself. Before long, we started dating and formed a new crew with some of his friends and people I’d met through Donny. We modelled ourselves after Calgary’s Aryan Guard, a neo-Nazi group known for its vandalism and white-power demonstrations. Our home base was a tiny bachelor apartment near Vaughan and Oakwood that we could barely afford to rent.

Members of different white-power groups weren’t friendly with one another. Most of us believed the same bullshit, but we didn’t get along, often yelling, “You’re not the real deal” so that we would have an excuse to fight. Members would sometimes leave one group for another, lured by promises of better organ-ization or better parties. Even members of the same crew, who claimed to have one another’s backs, would get into fist fights.

One Friday night, while our crew was partying at the apartment, a young woman passed out on a bed. Her ex, a drug dealer who’d just gotten out of rehab, went over and lay on top of her, groping under her bra and down her pants. My boyfriend and I pulled him off and started beating him up. When another friend tried to get between us, he took a blow to the face and hit the floor. He was unconscious for a while, and then, barely able to talk, he whispered, “Someone help me.” I was scared that he would die, so I left to find help. When I stumbled outside, covered in bruises and blood, two Black guys ran toward me, asking if I was okay. Even though I was clearly a skinhead, they offered to help, calling emergency services and staying with us until the ambulance arrived. They even gave us money for a cab ride back from the hospital.

I was stunned. Why were these guys helping us? Every narrative I’d been taught claimed that Black people were out to get us, but the opposite had happened. I realized that the hate I held was based on what I’d read and been told, not on interactions with real people. Their willingness to assist challenged everything I thought I knew. I’d experienced kindness where there shouldn’t have been any. For the first time, I was conflicted about my beliefs.

That same winter, our crew burned a Soviet Union flag that hung on the side of a Russian souvenir shop near the apartment. We saw communists, socialists and anarchists as self-hating antiracist white people. Our friend took pictures of my boyfriend saluting in front of the burning flag. Somehow, those pictures ended up on Anti-Racist Canada, a website dedicated to fighting bigotry, and we were all added to their watch list. The crew suspected I’d leaked the pictures because I’d been critical of their infighting and disorganization. Weeks later, after my boyfriend and I broke up, he and three of his friends confronted me about it. “We’re going to make this simple,” one of them said. “Take off your boots, give them to us and you’re free to go.”

Taking off my boots would be akin to handing in my resignation, so I refused. As I walked away, I heard footsteps behind me. I felt someone’s hands on my head and neck, and the next thing I knew, I was thrown into a brick wall. My head slammed full force into its rough surface. I fell to the ground and passed out. When I came to, dazed and in agony, somebody was pinning me down while several pairs of boots kicked me. I tried and failed to get up and escape until, finally, a security guard came toward us and I heard someone yell, “Run!”

Every part of me was hurting. My head pounded. I felt dizzy and shaky. My lip was bleeding, my knees and back throbbed, and my boots were gone. Luckily, St. Michael’s Hospital wasn’t far away, and I managed to walk to the ER. The doctor who saw me wasn’t white, so I was leery of him examining me. But he was kind, treating me like a human being despite my white-power tattoos. Once again, I was thrown off balance. Someone I’d been taught to hate was willing to overlook the differences between us. I knew I didn’t deserve his kindness.

The attack left me with a brain injury that affected my focus and short-term memory. As I recovered, my attackers spread rumours that I’d turned Antifa—anti-fascist, the total opposite of white supremacist—so I decided to get two new tattoos: a Norse rune that the movement had appropriated for its own use and “Our Race Is Our Nation,” referring to our wish to turn Canada into a white ethnostate. I wanted to prove to myself and everyone else that I was still in the movement. But deep down I was having serious doubts.

Clockwise from top left: the author at age 16; her “Racial Holy War” and Norse rune tattoos; with her then-boyfriend in their Oakwood Village apartment

I spent the next few

months bouncing between friends’ couches and shelters around the city: Eva’s Place, Covenant House, Second Base in Scarborough. My goal was self-preservation and I lived minute by minute. I didn’t bother looking for work. I spent the allowance that the shelters gave me on alcohol. It had been a year since I’d moved to Toronto, and I’d been drinking every morning and night. I thought I needed it to get through the day.

The movement gave me freedom, which was what I wanted, but I was desperately lonely. Most of the other guys had families they lived with or at least spoke to. I had no one. Their families let them make their own decisions and run their own lives; my mother seemed to hate me.

Several months after I left home, a friend of my mom’s included me in a group email, a joke she sent to several people. I replied, “Ha ha, thanks,” and she wrote back, “Contact your mom.” I wondered who had died—I figured that was the only reason my mom would want to talk to me. I sent her an email and was surprised when she wrote back. “It’s been very difficult for us,” she said. “We were very disappointed and upset with the breaking in and stealing of my cards. But I still love you and know that the daughter I’m proud of is still there somewhere.”

My mom and I kept emailing, and we eventually agreed to get together for my 19th birthday, in May of 2009. I had dinner with my family, and my mom gave me a new cellphone. Though the interaction was uneasy, it was nice to reconnect with her and my brother.

That summer, a friend invited me to see Kremator, a skinhead rock band, play a show in Etobicoke. There, I met Jan, a Hammerskin member visiting from BC. He and I got along right away. He felt like a long-lost friend. He was a few years older than me, extremely tall and well-built but gentle. Our conversations were rarely about white power. Instead, he wanted to talk about me and things I was interested in, like music and woodworking. I was sad when he returned to BC, but we remained good friends, emailing each other weekly for almost three years. While he never told me directly how disillusioned he was, I think we were both in the same place—tired of the movement but not yet ready to walk away.

As much as I wanted to stay in the city, I was sick of living on the streets, not having enough money for alcohol, food and rent. That fall, my mom offered to let me move back home on two conditions: that I turn myself in to the police for using her credit card and that I get a job or go to school. I agreed, so on the day before Halloween of 2009, she met me at the train station. As soon as we got home, she handed me her phone and said, “Make the call.”

When I did, I was arrested and taken to 17 Division in downtown Oshawa. I was charged with impersonation, forgery, possession of property obtained by crime, fraud under $5,000, and possession and unauthorized use of a stolen credit card. It was dead silent and cold inside the station. An officer walked me down a hallway lined with cells. He stopped before an empty one, opened the door and said, “All yours. Enjoy yourself.” It was about 10 feet by six feet with a small concrete ledge. There was a toilet with no water, no seat and no toilet paper. As usual, I was drunk. I shut down and time became a blur. Every minute felt like an hour.

An officer walked me to a tiny jail cell and said, “All yours. Enjoy”

When I was finally released, the next afternoon, my mom met me at the courthouse. The judge gave me a set of conditions to comply with. I knew two of them had been my mom’s suggestions: “You will pursue and attend education, training or gainful employment. And you will comply with all house rules.” I’d been away from home for more than a year and wasn’t sure I could follow her rules. But, by the time Christmas came around, I was happy to have a roof over my head. The house didn’t feel as much like a prison as it had before I left.

I turned 20 in May of 2010 and spent most of that summer completing my court-mandated 100 hours of community service at the local Salvation Army, where I could zone out while sorting through donated clothes and household goods. I attended drug-and-alcohol education classes, usually with the smell of booze still on my breath. I went out two or three nights a week, sometimes with my then-boyfriend and other members of the movement, drinking until closing time.

That September, I started studying cabinetmaking and woodworking at Humber College. I lived in residence, in a tiny private room with a single bed and a wooden desk. Eventually, the four or five hours I spent in class each day felt like a vacation from my outside life. In the movement, I’d often end up arguing with the guys over stupid stuff, but with my classmates, I didn’t need to compete to be heard. I graduated in September of 2011 and applied to the local carpenters’ union; acceptance required completing a six-week entry-level course. It was a struggle, in part because of the lingering effects of the brain injury from my beating, but I worked hard and was offered a job with a scaffolding company in Toronto as soon as I finished. The job gave me the self-esteem and confidence I had been desperately looking for.

Still, I kept in touch with old friends from my former crews. I considered many of them family. I emailed Jan every week, telling him about moving back in with my mom, getting a new job, guys I was seeing. He was non-judgmental, someone I could be honest with, say anything to. I griped about the way I was treated as a woman in the movement. Men scoffed when I told them I wanted to work in construction. They thought my job was to look pretty and procreate to perpetuate the white race. I even told Jan that I was bisexual, a secret I kept from everyone else in the movement. To them, being gay was unnatural.

One Saturday morning in March 2012, my boyfriend picked me up at the train station. “You know that guy Jan, from out west?” he asked. I hoped he’d tell me that Jan was returning to Ontario. Instead, my boyfriend said, “He died.”

Time stood still, just like it had when I lost my dad. Shivers ran up my spine. This couldn’t be true. When I got home, I googled Jan’s name and found exactly what I hadn’t wanted to believe. He had been stabbed to death. Police said it was the result of a break-in turned deadly and that there was no evidence linking his death to his involvement in white-power groups. Still, someone in the movement sent an email to the media, stating, “It was a hate crime against our people. We will not stop until there is justice for our fallen comrade.”

After Jan’s death, his mother posted an article on the Anti-Racist Canada website. She explained that he had been recruited as a young man but had distanced himself from the movement over time. “Jan was easy prey for a group looking for angry, blond and blue-eyed members,” she wrote. “[His recruitment] was the first time I lost my son. Now I have lost him forever.”

I thought black people were out to get me, but The opposite was true

Jan’s death brought me some much-needed clarity. Reading his mother’s post, I began questioning the victim mentality I had adopted for five years. My problems were not the fault of other races or religions. Plenty of other people had lost parents or felt like outcasts and hadn’t chosen to live a life of hate. I had no excuse. I was tired of being angry all the time.

In the summer of 2012, a few months after Jan’s death, I went to my final white-power show. I hadn’t yet told anyone that I’d decided to leave the movement. When a local band went on stage, their singer announced, “This is dedicated to our fallen brother, Jan.” It was like I’d been punched in the gut. They were using his death to promote their cause, something I found disgusting. I had gotten involved in the movement because it made me feel important. Now, I was starting to see things differently. I realized that if I died tomorrow, no one in the movement would really care. I went into the mosh pit, smashing around with everyone else. Thoughts bounced through my mind. Hate, I suddenly understood, was unnatural. Constantly having to warp every situation to fit the movement’s narratives was exhausting. Seeing the world through their lens hadn’t kept me safe. It had imprisoned me.

I decided I needed a change. I’d been drinking heavily almost every day since high school: after work, at home, at parties. The escape it offered had become my lifeline. I managed to stop, but I didn’t like myself or the world around me when I was sober. I was irritable, and every part of my body ached, like I had an unending case of the flu. But, for the first time, I saw all of the dysfunction that existed within the movement. I no longer found the parties interesting. The conversations were boring, the booze-sodden actions stupid. I realized that there had never been any real goals, any worthy causes in the groups and crews I’d belonged to. I no longer agreed with the propaganda I was being fed.

The author with her mother, Jeanette, at her childhood home, in Whitby

No matter how

eager I was to quit the white-power scene, exiting left a void in my life. I’d wrapped my entire identity around the movement. After I left, I started to question who I was. I received harassing calls and threats from members demanding that I stay. “Go fuck yourself,” were the first words I heard when I picked up the phone one night. “You’re a traitor.”

Befriending people who weren’t white was difficult at first. I had to change the hardwiring in my head. I found information online on critical thinking that prompted me to ask myself, Do any of those old thoughts make sense? No one had ever asked me to apologize for being white. There was no reason to fear or hate anyone based on their race, no reason to think that they were out to get me. I was the one who had been out to get them.

When the Unite the Right riot erupted in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, I realized that it wasn’t enough to get out—I needed to start making amends for the damage I had caused. I wanted to give back, to create change and to feel good about myself. I contacted Life After Hate, an American non-profit run by former extremists, most of them from the far right, that educates and reforms people wishing to disconnect from extreme ideology and become peaceful members of society. Through their network, I got to know others on the same road as me. It was refreshing to be part of such a group after years of trying so hard to fit in. With them, I didn’t need to change—they liked me as I was.

In November 2018, Life After Hate invited me to speak at a conference in Edmonton. As nervous as I was to share my story, I could see how helpful it was for people in the audience who had been through similar experiences. Since then, my mom and I have made it our mission to help other families like us. We’ve both spoken at events and assisted researchers with studies on hate. I now work full-time for Life After Hate and the Edmonton-based Organization for the Prevention of Violence, counselling former white supremacists on how to leave the movement, while my mom volunteers with Life After Hate’s family forum, a support group for parents and relatives of people who have joined extremist movements. Together, my mom and I wrote a book, Walking Away From Hate, which tells our story from both of our perspectives. With our publisher, we also created resource guides for parents and teachers. We want to provide people with the tools we never had and to help them understand hate—how people get drawn into it, how it recruits its members and how it is possible to leave and start again.

I’m alarmed by the rise of far-right groups like the Proud Boys. According to the Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism, there were approximately 100 right-wing extremist groups in Canada in 2015; by 2019, there were nearly three times that many. But I know first-hand that more and more people are leaving lives of hate too. When I meet with “formers,” I keep my own story in mind. I try to get to know them as individuals. I ask how their week is going, what’s new in their lives, and let them do most of the talking while I listen and try to understand what drove them to these beliefs in the first place. Listening, having an open dialogue and asking questions that challenge their mindsets and core beliefs works far better than arguing or shoving opinions down their throats. I don’t debate and I don’t judge. They don’t need to feel more ostracized than they already do. I am living proof that they can make it out.

After leaving the movement, I was troubled by my tattoos. Whenever I saw them, I was reminded of all of my past mistakes. Over time, I’ve had them removed or covered. The Celtic cross on my right arm became an hourglass wrapped in vines and roses, signifying how time heals. I covered the Norse rune with a candy skull and oak leaves, symbolizing Jan and another friend, who died by suicide. In August of 2019, I changed my last hate tattoo, RAHOWA (shorthand for “Racial Holy War”) between my shoulder blades, into a floral design of a cathedral window. It was a relief to see that toxic ink gradually disappear. Now, at last, I’m free of that chapter of my life and everything that went along with it.

This story appears in the January 2023 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here